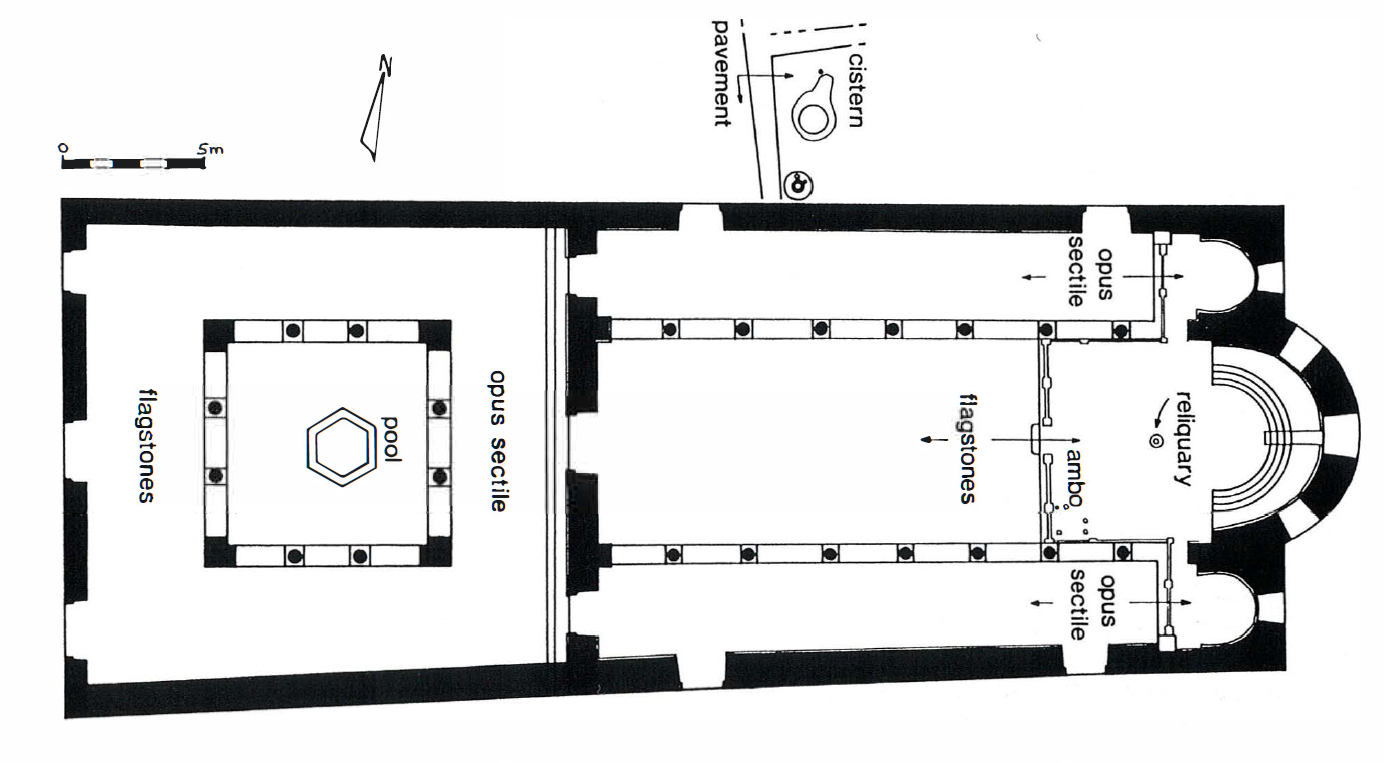

McNicoll, Pella in Jordan, 2, fig. 23 p. 154

Summary information

Characteristics

Classification

Roman

- Τ-shaped or bar-shaped chancel

- Tri-apsidal, aisles inscribed

- Altars in the side apses

- Relics and Reliquaries

- Ambo to the

northsouth? Baptistry outside off the atrium or the north aisle- Marble furnishings (high status imperial association) and imported fine wares

- Decorative elements on chancel screens

Separate north chapel

The Archaeology of Liturgy Project reflects research conducted at the W.F. Albright Institute of Archaeological Research in Jerusalem during the spring of 2023.