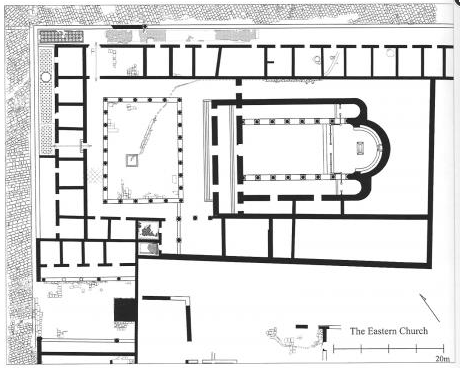

Remains of a church were built over a ruined temple in the late 5th or early 6th c. The church, which measures c. 62 x 29 m, follows the typical Christian basilical plan, with a rectangular prayer hall (19.93 x 18.25 m), an atrium to the west, and some additional rooms to the south. The church is oriented to the southeast, an orientation derived from the existing urban plan. Only the well-constructed foundations of the central and northern apses, constructed of cut stones bonded with gray mortar, have been preserved in situ, whereas the upper course, built of ashlars, has been partially preserved in the southern apse. The foundation wall forming the central apse is especially thick (2.40 m) and may suggest that it supported the wall delineating the apse as well as the synthronon.

A levelled and well-executed thick plaster floor was uncovered inside the apse, stretching over almost the entire area designated as the presbytery. Similar layers were uncovered near the lateral apses. Many mosaic chunks, mostly white tesserae, were collected during the excavations, mainly in conjunction with the central apse; two pieces bearing Greek letters may indicate that the plaster floor uncovered in the presbytery served as the foundation layer of the lost mosaic. Only a few architectural elements belonging to the church were found in conjunction with the building, including a Corinthian capital and two others decorated with crosses, one almost completely preserved.

A rectangular depression outlined by a few stone slabs, only two of which have been preserved in situ, was uncovered slightly north of the cord of the apse. This cavity, which is built like a box sealed beneath the floor, may have held a reliquary, presumably placed underneath the altar.

A spacious courtyard or atrium (c.25 x 27 m) is located west of the building, giving direct access, via a few doors, from the cardo into the building. The open courtyard was covered with stone pavers and surrounded by porticoes probably paved with white mosaics, as shown by several preserved segments. The stylobate supporting the columns was well preserved on the S, W and N sides of the courtyard. Two rooms paved with colourful mosaics in geometric patterns were exposed south of the courtyard. A plastered doorjamb, a single column drum and a threshold comprising several stone slabs, which were discovered in situ, are part of the doorway between the rooms south of the church and the corner of the atrium.

A comparison of the elevation of the floor preserved within the atrium and that of the foundation walls of the prayer hall indicates that the floor level in the latter was c.90 cm higher than in the former. The difference in elevation between the two spaces suggests that the prayer hall was erected on a podium and was thus higher than the atrium and nearby buildings. The difference could have been overcome by the addition of a few steps across the entrance wall or directly in front of the doorway leading from the atrium into the prayer hall.

From a thick destruction layer exposed north of the area, between the church and the shops and partially overlapping the latter came segments of stone architectural decorations and shattered pieces of marble. The pieces of marble seem to have come from the liturgical furniture inside the building, mainly in the presbytery; these include a chancel screen, a chancel post, and a stylized miniature Corinthian capital at the top of what appears to have been one of the legs supporting the altar. These elements are consistent with the character of the excavated church, which, to judge from its dimensions, was undoubtedly an impressive and lavishly adorned structure.

Edited from:

Zeev Weiss, “From Roman Temple to Byzantine Church: A Preliminary Report on Sepphoris in Transition,” Journal of Roman Archaeology, no. 23 (2011): 213–14.

Zeev Weiss, “Zippori 2015: Preliminary Report,” Hadashot Arkhe’ologiyot 128 (2016), https://www.jstor.org/stable/26679299?pq-origsite=summon.