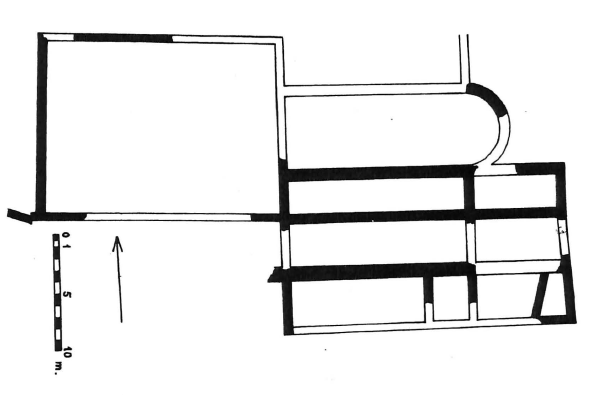

In the 1955 excavations, the remains of a Byzantine church with three wings, a pronaos, and a small monastery were found about half a meter below the level of the Crusader building. The monastery was situated south of the church and projected beyond the boundaries of the Crusader building. The Byzantine church closely resembles others from the fourth and fifth centuries, such as the Church of Gethsemane in Jerusalem. It contained several mosaic floors, of which only fragments have survived; they are sufficient, however, to reveal several repairs. The stylobate (0.9 m wide), which was raised above the mosaic floor, consisted of a double row of stones arranged in diagonal courses, held together by iron cramps. The perimeter walls (0.6 m wide) were built of only one row of stones laid in diagonal courses. The floor of the nave was laid at a different level from that of the northern aisle. (The Grotto of the Annunciation continued to serve as a place of worship instead of the northern aisle until the modern church was built. It was therefore impossible to excavate it.) Architectural elements (not found in situ)- for example, capitals decorated with crosses on all four faces- helped to clarify the plan of the Byzantine church.

From:

Bellarmino Baggati, “Nazareth,” in The New Encyclopedia of Archaeological Excavations in the Holy Land, ed. Ephraim Stern, Ayelet Lewinzon-Gilboa, and J. Aviram, vol. 3 (Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society & Carta, 1993), 1105.

Various architectural materials were found out of place including a base of a column and corresponding cushion, a small post for an altar or ambo, a fragment of an altar table, small post of a screen, panels fragments of screens with grapes, cross, and crown, fragments of inscriptions, a capital for a ciborium or iconostasis, and a small fluted column.

From:

Bellarmino Bagatti, Excavations in Nazareth, Publications of the Studium Biblicum Franciscanum ; No. 17 (Jerusalem: Franciscan Printing Press, 1969), 110.

Eleven different fragments of mosaic were identified in the excavation. Summing up the technical data, we find these characteristic marks: 1) the mosaic of the central nave (No. 1) appears singular in part on account of its extra-classical style, the only one to employ the colour vermilion, and rare for the promiscuous use of big and little tesserae. Very like to this is the mosaic of the little grotto (No. 3) marked by a great sobriety of colours. 2) The mosaics of Conon (No. 2), the lower one of the south nave (No. 4), that of the sacristy (No. 6) and possibly also that of the convent (Nos. 8-10), appear to be of the same material and style, judging from the size of the cubes and the use of classical motifs. 3) The upper one of the south nave (No. 5) is independent. 4) Also apart, on account of the roughness of its composition, is the mosaic of the atrium (No. 11).

The study of the mosaic subjects brings us to certain considerations. There are religious signs: the monogram cross and the simple cross in different forms. The former has two examples: within the crown and isolated: the latter is within squares, isolated and with other small complementary crosses. And so, the use of these signs does not appear as an isolated case, but the ordinary procedure. This leads us to the period prior to the decree of 427 of Theodosius II, forbidding the putting of the cross in pavements, although the order of Theodosius was not always observed, as, for example, in the mosaics of Jerash. The motifs used in the pavements, where the sacred signs are found, are known from other mosaics of 4th. and 5th. centuries. For example, the motif of the fish scales, as it is in the south nave, is frequently found in the octagonal basilica of Capharnaum, and in other places which can go back to the 5th. century as at Kh. Luga, or at ‘Ein Hanniya, Tabor, or to the 6 century as at Jerash. The motif of the crown was already in wide use in the Constantinian period. The motif of the squares decorated with zigzag lines, forming designs, and the squares themselves united by lines which crossed, as it is in the inscription of Canon, is known from the mosaics of Antioch, dated to the year 325.

From:

Bagatti, Excavations in Nazareth, 105–7.