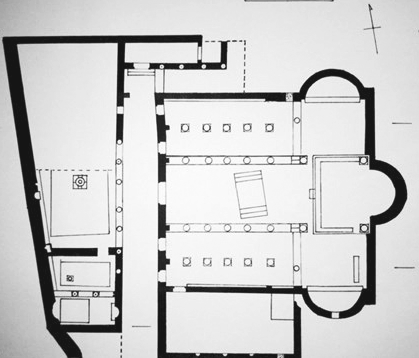

Contrary to our original projection of a rectangular structure here, this Byzantine basilica, cruciform in plan, is almost square, being ca. 32 min width (including the side apses), and ca. 26 min length.

Harold Mare, “The 1994 and 1995 Seasons of Excavation at Abila of the Decapolis,” Annual of the Department of Antiquities XL (1996): 262.

Just to the west of the south half of the central apse, the southern sector of the full three-sided iconostasis foundation was uncovered, in a central section of which on the west side the stone was cut to receive altar posts inscribing a central entrance way into the altar area. … The first two columns, one each on the north and south stylobates, at the western extension of the apse were column piers with Ionic capitals (engaged columns).There were also additional basalt column drums and capitals belonging to two additional rows of columns, one on the north and the other on the south of those bounding the central nave. The bases for these rows of columns were in situ and parallel to the extant inner rows of bases and columns, indicating that the basilica had five aisles; a central nave, and two side aisles on either side.

Harold Mare, “The 1992 Season of Excavation at Abila of the Decapolis,” Annual of the Department of Antiquities XXXVIII (1994): 366–67.

On the south were the lower courses of a south side apse, together with the foundations of an iconostasis screen and posts and two small sections of mosaic flooring; a small opening in the center of this apse on the south may point to the reuse of this section of the basilica as a mosque. The north side of the basilica produced lower courses of a similar north side apse, together with a mosaic floor within this apse. The archaeological evidence shows that the Area E basilica was cruciform in plan. …

An exciting find in the debris came to light: the team found the Abila Excavation’s first inscription inscribed on the bottom section of a long granite column which had been reused in the church; the inscription (studied and published by Bastiaan Van Elderen, the Staff Epigrapher) began with the familiar second century AD formula (found in inscriptions at Jarash), “Agathe Tyche”; the shape of the letters also indicates that inscription was composed the late second century AD.

Van Elderen’ s translation reads, “To good Tyche: For the safety of the rulers, .. … ……… Dischasdeinionus, having achieved his ambition, from his own expenses erected this column. He lived 26 [years].”

Our conclusion is that the column and inscription had decorated some public building, possibly a temple, and then the column was later reused in the church.

Harold Mare, “The 1994 and 1995 Seasons of Excavation at Abila of the Decapolis,” Annual of the Department of Antiquities XL (1996): 262–64.

The main and south aisle thresholds on the west side of the church were uncovered, together with a threshold leading from the south wall of the basilica into the south aisle of the church. Also the excavators here uncovered an additional room, with stone pavers, attached to the church just west and north of the north side apse of this cruciform basilica.

Harold Mare, “The 1996 Season of Excavation at Abila of the Decapolis,” Annual of the Department of Antiquities XLI (1997): 306

Some portion of the wall remains in place for much of the building. There are numerous drill holes with a diameter of two or three centimeters in the walls. Bronze hangers were found in two such holes on the west side of the west wall, held in place with plaster. These hangers apparently supported marble facing on the walls; numerous broken pieces of marble were found in the dirt fill throughout the church. …

The church has three apses, the largest apse on the east, and smaller apses on the north and south adjacent to the east wall, thus forming a cloverleaf pattern. Only the foundation remains of the east apse, which consists of concentric semicircular structures; the outside one is of limestone blocks laid with the long side along the circumference and flanked on the inside by limestone blocks with the long side laid radially. The radius of the apse is 4.28 meters, with walls 1.15 meters thick.

The south apse wall remains to a height of nearly two meters with radius of 3. 73 meters and wall thickness of sixty centimeters. An opening in the center of the apse wall extends from its upper surface to somewhat above floor level, a distance of 1.2 meters. The sides of this opening are irregular, with no evidence of doorjambs. The bottom of the opening is not flat, but slopes toward the interior of the church, with no evidence of a threshold.

The north apse wall is preserved to a height of about twenty centimeters with radius of 3.67 meters and wall thickness of fifty-eight centimeters. Some mosaic tile floor remains along the inside of the wall. The mosaic forms an inscription in black tesserae in a background of white tesserae. About one-third to one-half of the original inscription remains, made up of four separate sections of unequal length and spacing. Many of the letters of the inscription are complete, and some letters are incomplete but decipherable. …

Each apse is separated from the church sanctuary by an altar screen foundation, perhaps an iconostasis; only the foundations remain. Two marble altar screen posts were found; both were broken, but with the tops of the posts intact. A few small pieces of marble polished on both sides and thick enough to fit the groove of the foundation were found inside the church structure. The altar screen foundations for the north and south apses are laid straight across the open end of the semicircular walls, with upper surfaces near the level of the church floor. There is a section of the foundation at the west ends of both apses without a groove for the altar screen, providing entry into the altar area from the interior of the church. There is also a north-south altar screen foundation 3.4 meters long lying in the south aisle of the church 1.15 meters from the east wall. The groove and the post holes in this foundation are very shallow. This structure apparently constituted a worship center of some sort…

Nearly all of the floors in the sanctuary had been destroyed and carried off for other purposes prior to excavation, either for use in construction of other buildings or burned for fertilizer. A section of marble floor was found covering an area of approximately ten square meters in the southwest corner of the church. This floor may have been secondary, because the section of marble found does not abut the walls as one would expect, and it was laid around some limestone blocks that were clearly secondary. The presence of many broken pieces of marble and evidence for the use of marble facing on the walls suggests that the floors in the sanctuary were probably marble. The floors in the north and south apses were made of mosaic tile. The flooring in the central east apse and in the central altar area is completely unknown.

Clarence Menninga, “The Unique Church at Abila of the Decapolis,” Near Eastern Archaeology 67, no. 1 (2004): 42–48

Along the south side of the church is a large attached room to the west with a plastered floor entered from the southwest corner of the church. This large room (approximately 18m long and 10m wide) was constructed for ecclesiastical purposes and could accommodate a large group of people. Like the interior of the church, this room was originally paved with marble tiles at the western end. It also had a raised area of limestone pavers at the east end. The marble paved floor was largely broken up by falling masonry and was subsequently covered with a 2cm layer of plaster. In this second phase of the use of the room, it continued to be a large open area that could have accommodated a crowd. It also continued to be decorated with Christian symbols, as evidenced by a cross in the center of the western wall and a second one on a limestone column drum. Two large, rounded-topped, niches (approx. 1m wide, 35cm deep and 1.25m tall) were built into the southern wall of this room. While one niche was carefully plastered shut in antiquity, the other was left open and was used as a cooking or industrial fire pit in later times when the room’s roof had collapsed.

The room also contained a black marble reliquary that had been moved from its original location of use. The reliquary was found lying on the plastered floor upside down. When it was still functioning as a reliquary, it had been set deeply in a floor and stood proud about 20cm – as indicated by a mortar line that still adheres to the side of the stone. The cover for this three-chambered reliquary was not found. The shape of the bottom of the reliquary suggests that it had been carved from a capital.

David W. Chapman and Robert W. Smith, “Continuity and Variation in Byzantine Church Architecture at Abila: Evidence from the 2006 Excavation,” in Studies in the History and Archaeology of Jordan, ed. Fawwaz al-Khraysheh, vol. X (Amman, Jordan: Department of Antiquities, 2009), 528–30.

The architectural and artifactual discoveries in the Processional Walkways during the 2014 and 2016 excavations reveal a great deal about the ritual activities and the wealth invested in the Area E Abila Pilgrimage Complex. The plastered walls and expensive floors of tesserae and opus sectile were major investments, which contributed to the pilgrim experience. The mosaic and opus sectile paving add to the known corpus of decorated flooring from Abila. The mosaic pavements in the processional ways described here are consistent with other sixth to eighth century ecclesiastical mosaics found in the region, particularly the variously colored stones employed, which are common, while the hints of faux opus sectile mosaic patterns, exotic marble veneering and pavers bear testimony to the continuing affection for opus sectile. The inclusion of crosses and cross designs in the flooring affirms that it was not taboo to step on this religious motif.

The processional passages walked by pilgrims in the Abila Area E Pilgrimage complex provided access to highly controlled areas of ritual significance outside the central five-aisle church building. Passageways served as an ambulatory around the as yet unexcavated one-apsed ecclesiastical structure. The excavators anticipate that the mosaic paved corridor will continue north, before turning west to complete the circuit around the unexcavated northern focus of pilgrimages to the Area E complex. When that portion of Area E and the one-apsed northwestern ecclesiastical structure is excavated, the reason why Abila was highly venerated by pilgrims may be further clarified.

Robert H. Smith, “Preliminary Report on the 2014 and 2016 Excavations Revealing Processional Ways in the Abila Area E Pilgrimage Complex,” Annual of the Department of Antiquities, 2018, 658-651