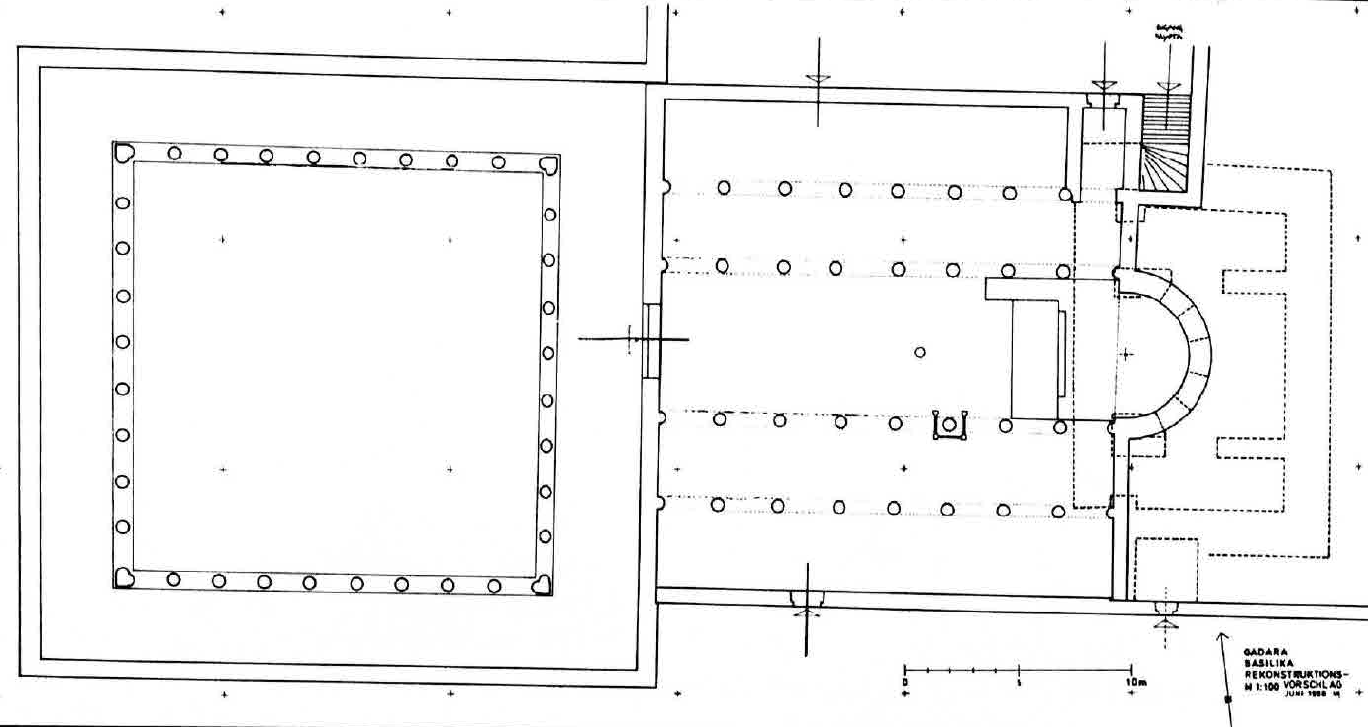

The church has a ground plan of nearly square shape measuring 21.50 m in the east-west and 20.10 m in the north-south direction. This huge ecclesiastical complex is oriented from east towards west with an entrance hall and a large open air colonnaded courtyard (atrium, 26.47 x 26.00m) in the west. The complex was framed by paved passageways along its southern and western facade. The building material of the whole complex consists of older (i.e. Roman) basalt and limestone materials from buildings in the immediate environs.

The foundations of the outer walls consist of a thick layer of opus caementicium and a row of well-cut limestone ashlars. As a common feature in Christian architecture, the orientation of the church was given by its apse which was entirely quarried for stone after the final destruction. lt was constructed on top of the semicircular base of the crypt. The purpose of this structure was to frame the central tomb of the Early Christian cemetery. The apse of the church provided the eastern border of the slightly raised altar zone (sanctuarium). From the sanctuarium, the central nave (aisle) extends axially towards the west and the light-window of the domed burial chamber of the pagan Roman mausoleum marks precisely its half length. The central nave of the church was separated from the lateral aisles on both long sides by an arcade consisting each of seven columns. The adjacent areas south and north of it were subdivided by one row of pilasters corresponding to the colonnades of the central nave. Thus, the northern and the southern sections of the church hall were divided on both sides into two lateral aisles.

On both sides of the apse, two doors gave access from the aisles III and IV on to a balustrade, probably made out of wooden beams, leading around the sacred space of the crypt on an elevated level. This construction allowed processions of pilgrims from inside the church around the venerated tomb which could be seen within the rectangular frame of the apse through the large rectangular openings. The southern and eastern limits of this processional walkway were were marked by walls. They separated procession area from an outer passageway, which gave access to a baptisterium in the southeastern comer of the complex. At the southern side, the floor of this passageway is partly supported by the ceiling of a barrel-vaulted chamber which could be entered from the southern facade of the church by a small door with a lockable monolithic basalt wing still in situ.

The interior of the basilica was originally made accessible through various entrances, the main one opening axially to the central nave. Additional doors, probably dating to a later use of the basilica, were found in the northern and in the southern walls.

The relatively narrow entrance was in front of the western facade of the building, that is the eastern colonnade of the atrium which extends over an overall length of 26.00 m immediately west of it. Its assumed width is estimated at ca. 26.50 m, so an approximately square courtyard may be reconstructed.

The interior space in the courtyard was framed on all sides by a colonnaded hall, the stylobate of which came to light in the section of the long probe. The cross-section of these halls measured 3.80 m. While the floor of the atrium was entirely destroyed by recent army bulldozing, the floor level of the narthex (and probably of the colonnades of the atrium) was once covered by a fine pavement made of smooth rectangular basalt slabs.

Weber and U. Hübner, “Gadara 1998. The Excavation of the Five-Aisled Basilica at Umm Qays: A Preliminary Report,” Annual of the Department of Antiquities of Jordan XLII (1998): 446-449

Four marble column bases of Attic-Ionic type were uncovered in the central aisle, flanking the western end of the altar zone. These marble bases supported column drums of Troas granite with Corinthian capitals made out of marble from Proconessesus.

Grooves chiseled into the upper surfaces of limestone blocks testify marble chancel screens, three poles of which have been found reused in masonry put in the western part of the central nave. Fine marble slabs originally screened not only the altar but were extended on both sides to the west towards the central nave. The third column base (counted from the east) of the southern arcade was surrounded by marble slabs as well. One could assume that this has been done in order to support a reliquary or tabernaculum fitted to the column at this emphasized spot of the church. Some of the marble slab fragments, found in the mosaic floor close to the main entrance, could be identified as part of a mensa placed on top of the altar.

The interior of the basilica was embellished with a large mosaic pavement. The style of its geometric ornamentation and the few figural motives suggests a date in the sixth century AD.

Weber and U. Hübner, “Gadara 1998. The Excavation of the Five-Aisled Basilica at Umm Qays: A Preliminary Report,” Annual of the Department of Antiquities of Jordan XLII (1998): 450