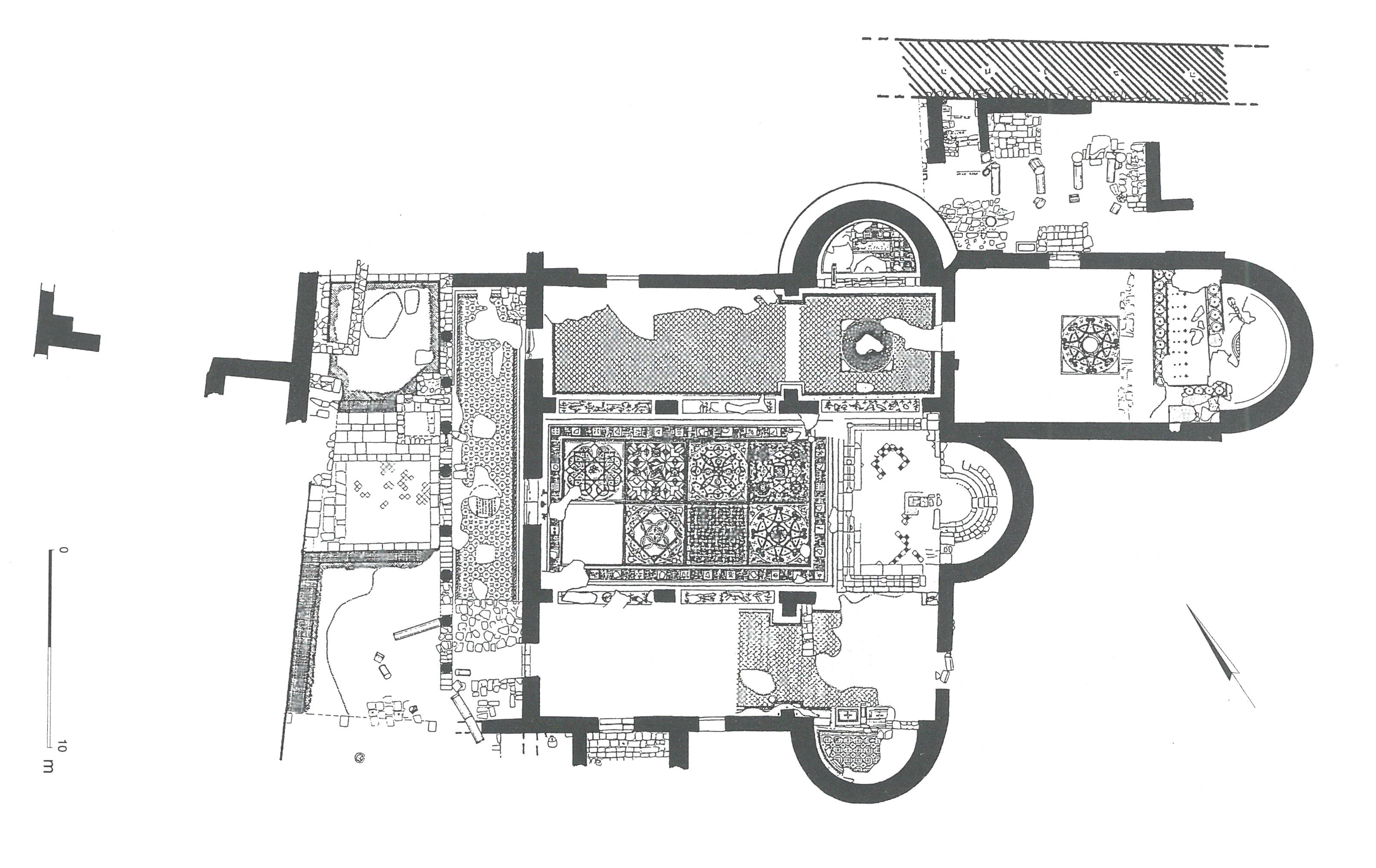

The newer church (Church of the Martyr) is larger, also built as a basilica with two rows of arches dividing it into a central nave and aisles. The three apses to the east were arranged as a trefoil, the central apse containing a synthronon and a bema, at the center of which stood an altar. Below the floor of the bema, paved with colored stone tiles, were found the remains of a reliquary. Chancels once stood in front of the bema and on both side apses. The northern apse contained a decorated marble sarcophagus, which probably originally stood in the cellar of the central apse of the small church outside the wall, and was moved to the new church when the former was destroyed.

Benny Arubas, Gideon Foerster, and Yoram Tsafrir, “Beth-Shean: The Hellenistic to Early Islamic Periods,” in The New Encyclopedia of Archaeological Excavations in the Holy Land, ed. Ephraim Stern et al., vol. 5 (Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society & Carta, 2008), 1634.

The church consisted of a narthex, a lateral chapel and a refectorium.

The narthex (11 x 23 m) was bisected by a stylobate carrying eight limestone columns (diam. 0.5 m) with crosses on their capitals. Doorways in the north and the south led into the narthex’s west part, backed by a wall. The central section of the west part of the narthex was paved with slabs of marble and bituminous limestone, while both its sides were paved with white mosaics. The east part of the narthex, from which three doorways led into the nave and the aisles, had a colorful mosaic floor.

Two rows of arches separated the nave from the aisles. The nave (9 x 15 m), the aisles (5.5 x 20.0 m) and the north apse were paved with mosaics. The base of the column which supported the ambo was identified in the northeast corner of the nave. A marble-lined sunken square in the front part of the central apse and under the presumed site of the altar had probably contained the reliquary. The central apse was paved in opus sectile style with colorful stone tiles. Marble chancel screens decorated with interlaced designs and a cross, as well as marble screen colonnettes were also recovered in the front part of the apse. Additional decorated marble chancel screens and colonnettes, were found in front of the south apse.

A chapel in the northeast part of the church consisted of a long hall (7.8 x 15.0 m) with an apse (diam. 5.5 m). A stairway along the south wall led to the second story. A masonry-built and plastered baptismal font was uncovered at the southeast end of the chapel. Many pottery store jars and some bronze pots were recovered in the chapel and the narthex.

A doorway in the center of the north chapel wall led to the refectory, located between the chapel, the north apse and the city wall. This hall, which was only partially exposed, was bisected by a central row of columns. A stairway in the east led to the second story. The floor was paved with basalt and limestone slabs. A kitchen at the northwest end contained an oven (tabun), a work surface of marble slabs, and pottery vessels. The heads of two busts, of the Roman-type burial head stones well known at Bet She’an, were found in the refectory, where they were apparently used as building material.

The mosaic floors in this church are of excellent quality and display a rich variety of motifs. The colors in all the mosaic floors are the same and are restricted to only eight colors or shades-white, black, gray, pink, two shades of red and two shades of ocher used to produce a colorful effect. The density of the tesserae varied from 20 to 40 per sq dcm in the narthex to 80 to 100 per sq dcm in the nave.

The white mosaics in the narthex were laid in a herringbone pattern. The mosaics in the inner part of the narthex had a design of squares and octagons in a braided border. A medallion set into the mosaic floor opposite the main entrance contained a seven-line Greek inscription; the north part of the inscription did not survive, but the remaining segment attests that the church was dedicated to a martyr whose name has not been preserved. Two birds flanking a krater are represented in the mosaic floor next to the threshold. The mosaics in the nave included eight carpets, arranged in pairs within a rectangular frame filled with a design of meanders and squares; the squares contained representations of fruit and vegetables and flowers at their margins. Each pair of carpets was decorated with complex geometric designs: one of each pair was set into a circle while the other filled an entire square. The carpet pairs are arranged so that the two kinds of design shapes alternated. The long panels in the intercolumniations contained representations of animals and plants, as well as hunting and pastoral scenes (Color Plate); some of the figures were defaced.

Both aisles had identical mosaics with a scale-and-bud pattern, an interlaced border and lozenges at fixed intervals in the white edges. The north part of the transept had a square panel containing a closed circle; the south part of the transept, which has not been preserved, must have been similarly decorated.

Gabriel Mazor and Rachel Bar-Nathan, “The Bet She’an Excavation Project – 1992-1994,” Excavations and Surveys in Israel 17 (1998): 30–31.