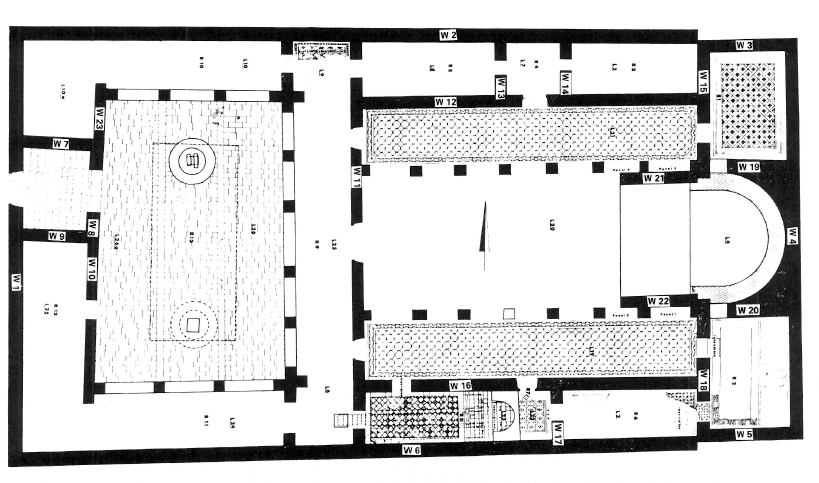

The church included a large basilica, an apse with flanking pastophoria, two lateral wings containing auxiliary rooms and chapels, a crypt, a narthex and an atrium.

The church was built and completed in one phase. At a later stage, slight alterations were carried out in some rooms. The domus, or prayer hall, was here designed along the principles of the standard Byzantine basilica: a hall, divided by two rows of columns into nave and aisles; the width of the nave, which spanned the apse-base, almost doubled that of the aisles. The entire hall, including the apse, measured 24 x 15 m, proportions similar to those of most Byzantine churches.

The three entrance doors set along the western wall correspond to the three internal areas. The central entrance, 2.20 m wide, had a double set of doors; the two side entrances had single doors, 1.10 min width. Each colonnade consisted of six freestanding columns and a respond on either end. A stylobate was not provided, and each of the bases was set directly onto plinths sunk below floor level. The intercolumnar intervals were 1.75-2.25 m wide. The portions of the nave mosaics which were preserved suffice to suggest an elaborate, finely executed, design. The mosaics along the aisles, which apart from iconoclastic destruction were entirely preserved, displayed a rich variety of colors and themes.

The chancel area was paved with slabs of stone (perhaps of marble), as suggested by impressions in the bedding. The solea was built on a platform raised 20 cm above the floor of the nave. The apse was set off from the solea by a step 20 cm high. In the center of the apse were the remains of a limestone reliquary (65 x 35 cm), set below the floor into a depression 35 cm deep. Along the interior of the apse was a basalt bench (one meter wide, 0.25 m high), the clergy’s synthronon. The central portion of the bench was slightly elevated, perhaps indicating a higher seat, probably the bishop’s thronos.

Three sockets of the chancel screen base were preserved which carried the chancel screens, of which only fragments were preserved. The white marble fragments suggest that the screen design consisted of a Greek cross set within a wreath.

The construction of the inscribed apse produced two equal (6 x 4 m) flanking rooms. The rooms were entered through openings from the side aisles, although the original plan also provided for access from the apse. For some reason, and at a time difficult to determine, these passages were blocked off. The northern pastophorium was well preserved. Its walls stood to a height of 1.5 m and on some were preserved segments of painted plaster. The pavement of the room consisted of a central mosaic panel and a smaller panel at the threshold. There were no signs of a door, and the room probably remained open to the aisle. 15

The southern pastophorium was identical in construction. But during the second half of the sixth century, this pastophorium was remodeled to house a baptistery. A dedicatory inscription was found at the entrance from the southern aisle. In the last five lines of the inscription the dates of the work are given. The dating was calculated according to indictions and according to the years of the reigning emperor, in this case, Mauricius Tiberius (582-602 CE), and, more precisely, during his first consulate. If we accept that the tenure was five years, we may suggest that the mosaics were laid during the first five years of the reign of Mauricius, i.e., 582-587 CE.

Only the lower portion of the font was preserved. Originally, it was oval (45 x 25 cm) and plastered within. The relatively small basin (45 cm deep) had a drain on its western edge.

Flanking the basilica on the north and south, were two symmetrically arranged wings, each containing two long rooms with a small square chamber in between. The northern wing consisted of two rectangular chambers (each 7.5 x 3 m) and a central square hall (3 x 3 m). No traces of mosaics were preserved, perhaps as a result of the conversion of the entire wing into an oil press.

The Southern Wing was planned similarly to the northern wing, but it underwent changes also. These changes seem to have been of a liturgical nature. The plan of the eastern room remained undisturbed, apart from an opening which was made in order to connect it with the baptistery. It was difficult to determine whether a new mosaic was actually laid at this time, as most of the pavement was destroyed, except for a small portion in the easternmost part of the room. Possibly, this room functioned as a forecourt of the baptistery. It is also necessary to assume that the small square chamber, which provided the only western access to the forecourt, was also part of the complex. Thus, the baptistery seems to have included three rooms: a small entrance chamber, a large hall, and an inner chapel.

In the western room of the southern wing and in part of the small square chamber, a small chapel was established. As the two inscriptions within the chapel were destroyed, the date of this addition is not as

clear as that of the baptistery. Yet, it is plausible that both were authorized and established at the same time.

The chapel consisted of a prayer hall (5.70 x 3 m), a small solea (1.30 x 3 m), and an internal apse (2 x 1.40 m). Entrance to the chapel was from the narthex and also from the western end of the southern aisle. This entrance was at some later time blocked, almost entirely destroying an inscription within a tabula ansata. The mosaic floors of the chapel were in black and white tesserae. The chancel was set off from the nave by a low step on which the screen was secured in grooves cut into the stone. A narrow entrance of 40 cm provided the only access to the apse area. The altar originally stood in the center of the apse, close to the screen, as indicated by the disruption of the pavement.

At the southern end of the narthex, in front of the entrance to the southern wing, was a flat basalt stone with an iron handle. This sealed off an entrance to an underground passage. The passage consisted of a shaft, one meter wide and two meters deep, with a staircase of six steps leading to a vaulted crypt. The crypt (6.25 x 2.40 m, over 2 m high) occupied the same area as the rooms above. Within the crypt were burial troughs, three on each of the long walls, leaving a narrow, central aisle of 70 cm. The two westernmost troughs were empty, suggesting that they had never been used. The central troughs contained eight burials, while the eastern two contained over twenty individuals. On the wall was an incised composite cross.

The atrium measured 13 x 18 m, occupying almost half of the church compound. The atrium included a large, open court, surrounding porticos and a small entrance chamber. The entrance chamber and the court were paved with large, finely dressed basalt slabs.

Vasileios Tzapheres, “The Excavations at Kursi–Gergesa” ‘Atiqot, no. 16 (1983): 5-14.