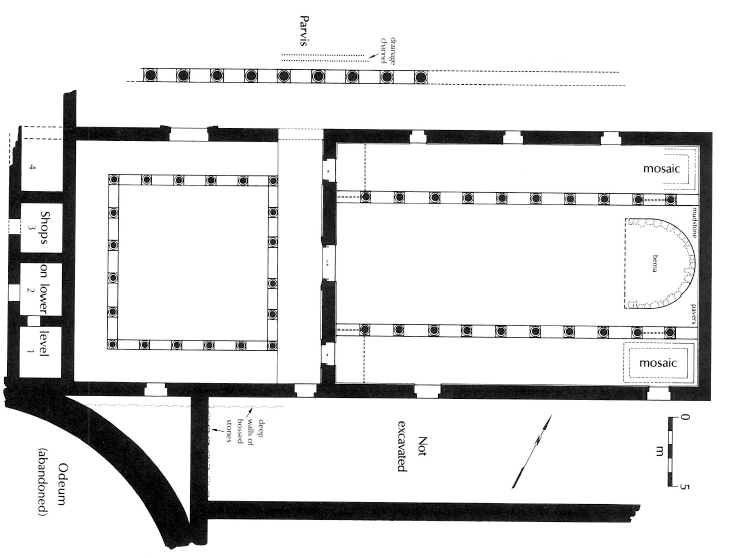

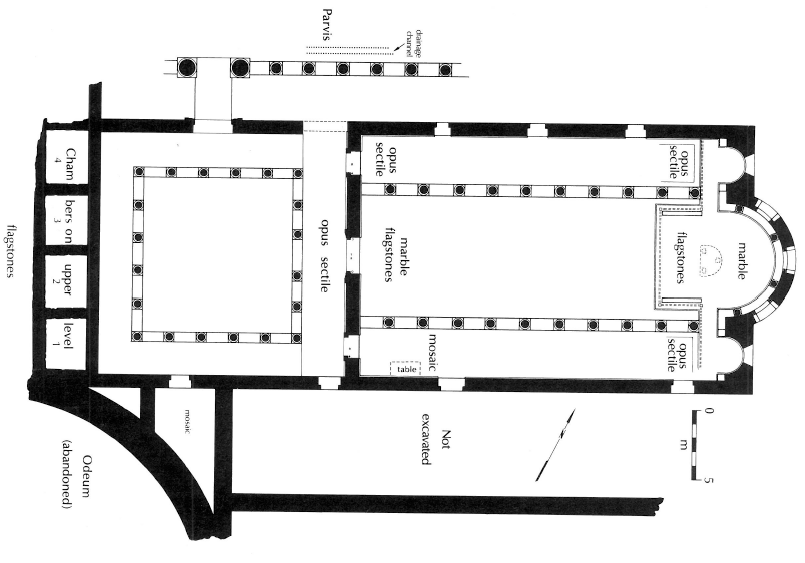

Excavation revealed that the sanctuary of the Church was a rectangular building with three apses at its east end, of which the central apse projected from the rear of the building, the north and south apses being inscribed in the east wall. The exterior width was 19.25 m and the length 29.65 m (originally about 28.15 m), exclusive of the central apse; the interior was 17.45 m wide and 26.10 m (originally about 26.35 m) long, exclusive of the apses.

The ashlar walls of the Church were less solidly constructed than those of the Early Roman period in the area, and were not entirely uniform, varying in width from 0.80 to 1.00 m but generally being about 0.90 m wide. The apses, which were constructed at a later time, had relatively well-hewn stones that were cut appropriately to fit the walls’ inner curvature, and any crevices between the blocks were chinked with small stones and mortar.

The main entrances to the sanctuary-located, as would be expected, in the west wall-were approached from the colonnaded atrium. There were three doorways on the west front, with three corresponding aisles on the interior. The large central portal, 2.32 m wide, had a finely-shaped surround of Ajlun limestone in simple Roman style. The north wall of the sanctuary had two well-preserved doorways. The south wall had two entrances, which were wider and not directly opposite those on the north. The easternmost of these was situated very close to the south apse. The position of the reveals showed that this door opened outward, whereas all other doors of the sanctuary opened inward. It is reasonable to suppose that this door was not intended for public use, but led into a baptistry, chapter house or clerical apartments.

The aisles of the sanctuary differed slightly in width, the north aisle being 3.62 m wide to the edge of the stylobate and the south aisle 3.40 m. The colonnades that formed the aisles rested on stylobates consisting of large, well-cut, fine-grain limestone slabs, which were slightly raised above the floor. Three column bases of the north colonnade and five bases of the south colonnade were excavated. The original intervals can be calculated to have been 2.45 m from center to center, with ten columns in each row. All six of the capitals recovered in the sanctuary appear to have been spolia, as their varied styles indicate.

Three basic kinds of paving were found in the sanctuary: marble flagstone, opus sectile and mosaic. The nave was paved with flagstones of blue-veined Thasian or western Anatolian marble. Even before the north and south apses were constructed, the northeast and southeast corners of the sanctuary were given prominence. Although apparently separated from the rest of the sanctuary only by marble screens, these locations served special functions, as the polychrome mosaic floors installed in them indicate. In a later phase, probably after the mosaic paving had been damaged in earthquakes, the apse floors were raised 40 cm, and the aisle floors were at least partly repaved with either white mosaic tesserae or opus sectile. The raised apse floors were paved with marble flagstones laid on a gray cement bedding.

In every phase of the Church’s active existence the sanctuary was divided into areas of greater and lesser sanctity. The chancel was set apart from the rest of the sanctuary by marble parapets, and there were other internal divisions as well. Some of the bases of the columns in the sanctuary had wide vertical slots cut into them to accommodate such stone screens. Screens inserted into the slots thus would have created rectangular enclosures at the northwest and southwest corners of the sanctuary, accessible from the portico but not permitting deeper penetration into the sanctuary.

After the renovations which transformed the pastophoria at the east end of the north and south aisles into apses with raised floors, it was necessary to redefine the especially sacrosanct spots within the Church through the use of screens. In the raised paving of the south apse were found square cuttings that had accommodated posts for screens; indeed, a fragment of a post was found embedded in one of the holes. Since there was no evidence of an opening leading from the north apse to the north aisle, the apse may have been accessible only from the chancel.

As originally constructed, the chancel was a low, freestanding semicircular platform which anticipated the semicircle of the central apse that was later built at the east end of the sanctuary. It was positioned slightly to the north of the axis of the sanctuary.

Because of numerous alterations to the chancel over the centuries, most of the evidence for chancel screens comes from the later history of the building, although screens from earlier phases were probably re-installed in various ways during subsequent remodelling of the sanctuary. Only one fragment of a marble chancel post was in situ, all that remained were the square cuttings for the posts and the grooves left behind when the screens were removed. The only remnants of screens found in situ, in the Church were those on either side of the chancel, and these consisted only of pieces of their lower portions that remained embedded in their grooves in the floor; these screens were, however, of high quality, consisting of fine white marble handsomely carved in open lattice-work with stylized floral patterns

Fairly early in the history of the Church, 45-cm-high benches were installed on the north and south sides of the chancel, directly behind the east-west chancel screens and on top of the gray bedding. Although fashioned of varied stones, some of poor quality, they were veneered on the top and sides with slabs of Ajlun limestone, fragments of which were preserved at the west end of the northern unit. The most likely explanation for these structures is that they were benches for presbyters. The need for such seating would have existed even after the construction of the synthronon in the central apse, since that structure could not have accommodated seating other than the bishop’s throne.

Around the inside curve of the central apse of the Church was a bench 1.40 m high and approximately 1 m wide, constructed from reused ashlar blocks of varying quality and size, poorly laid. The top of the bench was missing, but its original height could be determined from the state of the apse wall behind it. At the center was a rather crudely built stairway of five steps, imprecisely aligned with the east-west axis of the sanctuary. The bench and its access stairway were faced with a variety of marble slabs, some of which were found in place.

The altar of the Church had been removed after the earthquake of A.D. 717, along with all other furniture in the Church, but its location can be inferred with considerable plausibility. Two stages were discernible. Excavation below the latest floor of the bema revealed two 14-cm-square holes in mudstone blocks set in cement on the east edge of the installation of the screen and a third similar hole in a poured-cement block near the axis of the chancel but farther east; together these holes formed a triangle that supported the legs of an altar table. In a later stage, when the bema had been enlarged, the altar may have been moved westward about I meter, to stand above a carved marble slab that had been embedded horizontally in the floor.

The atrium was a colonnaded courtyard adjoining the sanctuary on the west, sharing the Church’s west front as a common wall. Its internal dimensions, including the porticos, were approximately 17.45 m north-south and 17.80 m east-west. It had porticos on all four sides, of which the eastern was wider than the others. The unroofed central courtyard enclosed by the porticos measured approximately 11.20 m north-south and 10.90 m east-west. As originally built, the Church may have had a portico only on its west front, the full atrium having been constructed at a slightly later time.

The major entrance throughout much of the Church’s history was through the portal in the north wall of the atrium. That doorway, 2.80 m wide, was the most elaborate one in the Church, embellished with a limestone surround, probably one of Roman date that the builders appropriated from an earlier structure.

Robert H. Smith and Leslie Preston Day, Pella of the Decapolis (Wooster, Ohio: College of Wooster, 1973), 37-53.