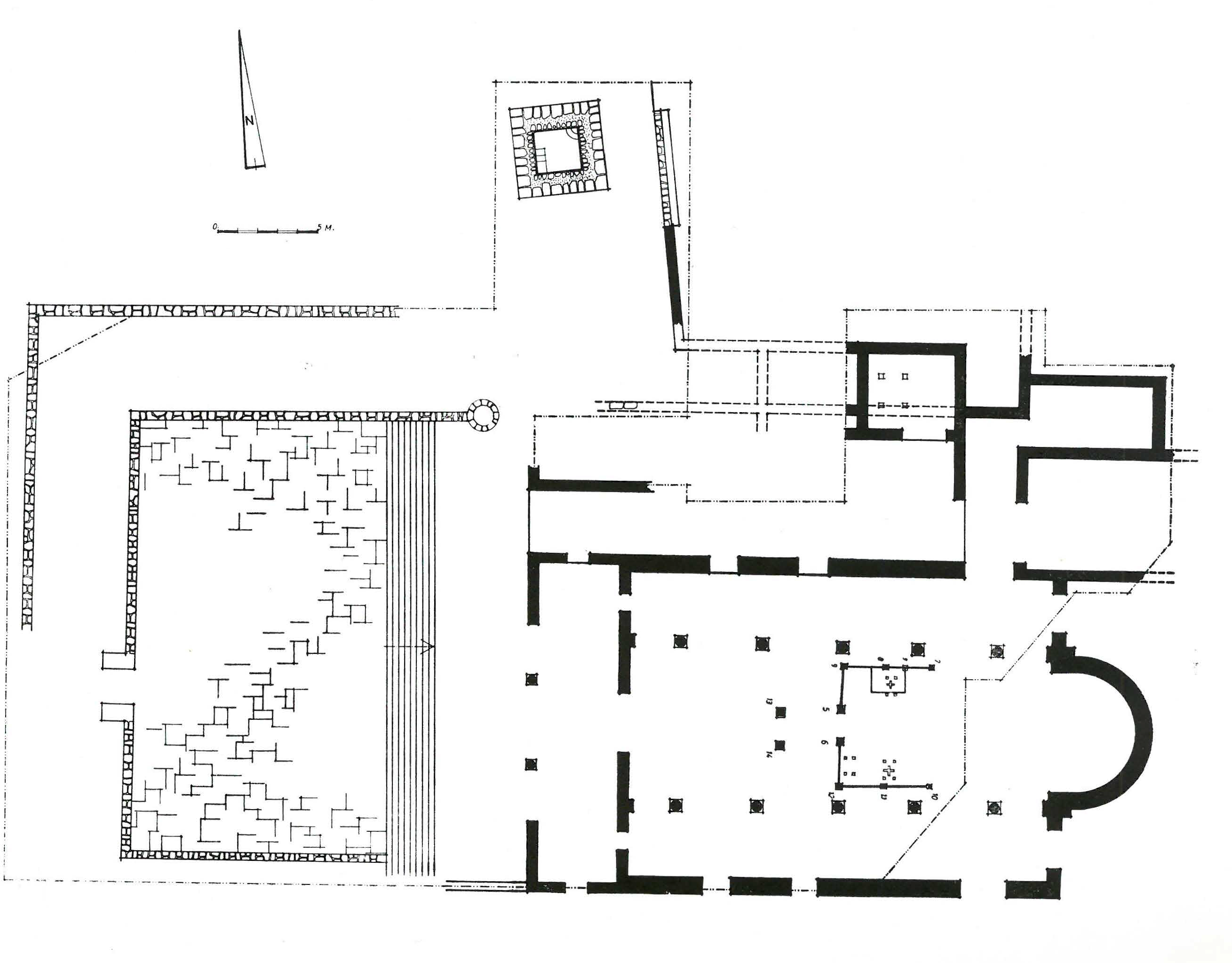

The church is of the basilican type, with a northern and southern aisle and central nave. To the west a flight of steps led from the atrium to the terraced summit of the hill, on which the church, the northern courtyard and adjacent buildings were erected. The church is orientated almost exactly towards the east.

The atrium was surrounded by porticos. The western gateway was erected south of the center of the atrium, yet opposite and in line with the main door leading into the central nave of the church. The western facade of the enclosing wall of the atrium was at least 30 m. long.

The narthex floor was covered with a mosaic which was dated by an inscription to the 5th century. In Phase I the terraced outer narthex and the continuation towards the north of the narthex formed one large continuous porch which turned and continued in an easterly direction alongside the northern wall of the domus. In Phase II a stylobate with two columns separates between the narthex and the exonarthex. The exonarthex extended much to the north relative to the narthex and the domus. From this extension a corridor led to the east, parallel to the northern wall of the church. The narthex, at its northern end, also had an entrance to this corridor.

A flight of steps led from the atrium to the church itself, which, together with the northern courtyard and adjacent buildings, were erected on top of the hill. A large amount of broken window glass was recovered from the floor of the church. As a result of the fire which ravaged the building most of the glass windows were fused. Also, the glass paste tesserae from the walls were often totally burnt. The walls, the pillars and the roof collapsed at the time of the last destruction. Thousands of broken roof tiles were found littered on top of the charred remains.

The charred remains of wooden doors, including metal parts of door fittings, locks, handles, nails and even a bronze door hinge, were found between narthex and exonarthex and at the central western entrance from narthex to nave. The hinge was found in the fill underneath the floor and must have belonged to the earlier building period.

The central entrance from the west was apparently very wide, as can be ascertained from the width of the inscription in front of the threshold. The valuable stone sills and doorjambs had apparently been torn out by stone robbers. Only the negative evidence of the damaged mosaic floor of the doorways indicates the place where the doorways and passages had been.

Though, unfortunately, the evidence is only indirect, it seems that after the second church building period worshipers gained entrance into the church from the narthex through three portals. The southern portal must have been just south of the Greek dedicatory inscription of the outer narthex, which might explain its location midway between the central and southern entrances. A side entrance, probably still dating from the first building period, connected a corridor leading from the western forecourt (the atrium), through the interior northern forecourt – the L-shaped court – into the narthex. Two side entrances also from the north, could be seen leading from the L-shaped court into the center of the northern aisle. No trace of the opposite entrances through the south wall of the church could be observed except for a decorated edge probably indicating a side entrance. As the buildings south of the church have not been excavated and as mosaic floors are known to exist adjacent to the south and to the southeast corners of the church, it must be assumed that doorways were built into the south wall to connect the adjacent buildings with the church.

The church domus, excluding the outer narthex, was erected on an area of approximately 32 x 16 m. We have thus a proportion of width to length of 1:2. It seems this proportion is common for elongated basilicas in the 4th and early 5th centuries C.E. The aisles are long and narrow, 2.7 m. in width. The width of the intercolumnary space is 1 m. and the nave is 7 m. wide.

Unfortunately, few bases or columns were found in situ. The capitals of the colonnades as well as those of the narthex were uniformly of the Corinthian order. The early type of Corinthian capital from Shavei Zion is usually attributed in the Roman world to the 4th century C.E. and to the 1st decades of the 5th century C.E.

The narrow aisles at Shavei Zion are separated from the central nave by two colonnades of five columns each. The nave itself is divided into six bays. Only remains of four columns were found in situ. The distance of the easternmost column and the westernmost column from the pier of the apse and from the western wall is 2.80 m. each, while the distance from the center of the column base to the center of the next column base is 3.80 m. – 4.00 m. Fragments of columns and capitals were found lying as they fell on top of the mosaic floor.

Altogether 14 post holes were found in the eastern half of the nave. In the 3 sets of 4 bases, each originally supporting small slender marble columns were found within the screened area of the nave in front of the bema-apse. It could immediately be seen that 2 sets of 4 pedestals each grouped around a cross were contemporary with the original floor mosaic. The third set of 4 column bases without a cross in the center, was set into the original scale pattern without any effort being made to frame the bases or to restore the original pattern .

In the first arrangement of post holes in the chancel area, the two crosses, each surrounded by four columns, were outside the enclosed area, i.e., in front of the bema and apse. The four marble columns undoubtedly served as the support of a table above the crosses. Similar tables are known to have been in use as altar or mensa or pulpit.

The north-east chapel was placed parallel to and north of the east end of the domus. Two different mosaic floors found super-imposed one upon the other indicated two building periods. A layer of fine debris and ashes separated the lower mosaic floor from the upper. The eastern part of the later chapel was destroyed together with the apse just before excavations began in 1955. Fortunately, when 8 years later the upper mosaic floor was lifted, the foundations of the north-east corner of the earlier chapel were found to have escaped destruction.

In the 2nd, later, building period the chapel was enlarged to measure 5 m. south to north and at least 6 m. from west to east. The lower chapel had been a square with sides of approximately 5.20 m. The later chapel could only be enlarged towards the east, as the domus to the south prevented expansion in that direction.

A corridor connected the eastern end of the northern aisle with both the early and the late chapel. The western entrance into the chapel was changed in the later period.

The whole of the Shavei Zion church and its annexes were paved with mosaics, except in the small areas where stone slabs were used, and the atrium. The pavements found are not, however, homogeneous; in fact, three distinct periods can be distinguished in them, with some doubtful cases. The find of an earlier pavement, 10-12 cm. below the later one in the north-eastern chapel, corresponding in style and execution with the pavements of the first period found in the nave and aisles of the church itself, makes the sequence of styles one and two quite certain. The pavement of the third period in the exonarthex is dated by an inscription, but dates of the first and second period have to be argued on stylistic and historic grounds.

Prausnitz and Avi-Yonah, 18-29