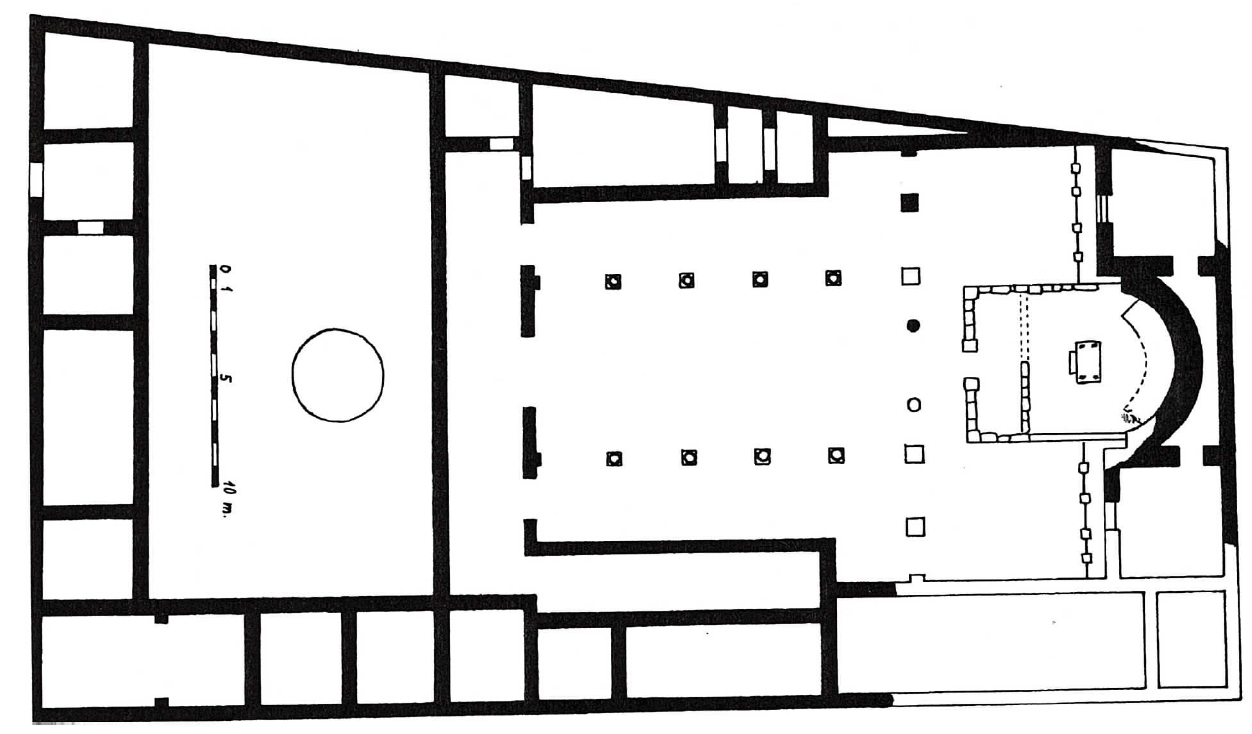

The length of the church, court, and hospice complex was 56 m from north to south, 33 m on the west, and 24.3 m on the east. The church (25 by 19 m) was a basilica with a transept. The level of the prayer hall was 0.3 m above the narthex and 0.5 m above the atrium. The walls (0.6-0.95 m thick) are built on foundations 0.8-0.95 m wide and preserved to a height of 1.45 m. Except for the sills and stylobates (which were of white mizzi limestone), the complex was built of local, roughly dressed basalt, covered on the interior with mortar (a mixture of cement and lake sand), in which ribbed potsherds were set. The top layer was plaster mixed with straw and was painted red.

The church had a straight eastern wall. Between the eastern wall and the rear wall of the apse (1.2 m wide with a radius of 3.3 in) was a narrow corridor. The apse was flanked by two rooms. The presbytery (6.9 by 6 m) extended in front of the apse and was separated from the nave and transept by a chancel screen. The altar stands in front of the chord of the apsidal arch. It was shaped like a table, resting on four square legs. According to Peter the Deacon (who reports Egeria’s description), the stone on which the Lord placed the bread had been made into an altar. People who went there took away small pieces of the stone to bring them prosperity. Below the table was a block of undressed limestone (1 by 0.6 by 0.14 m). Traces of a metal cross and the limestone’s chipped appearance mark it as the traditional “mensa (table) of the Lord.” Behind the altar, a semicircular seat (1.1 m wide) served as a synthronos for the clergy.

A transept projected 1.75 m on either side of the front of the presbytery. A row of four pillars separated the transept from the nave (7.9 m wide). The central two pillars bore an arch that collapsed in an earthquake. The central pillars were reset, with a narrower range for the two supporting the arch in the nave. This, and the enlarged chancel screen, were the main later additions.

Two aisles (each 3.58 m wide) were separated from the nave by two rows of five columns each, set 3. 3 m apart. The main entrance was probably 3.2 m wide, and the aisle en trances, 1.85 m. A narthex (3.3 m wide) led to an atrium in the form of a rough trapezoid (23 by 13 m) surrounded by the rooms of a hospice on the east, south, and west. A diagonal wall, slightly below the level of an ancient road, closed the complex on the north. A cantharus (diameter, 5 m) stood in the center of the atrium.

Subsequent excavations showed that the step crossing the bema from north to south was apparently not from antiquity, but was created when the mosaics were extracted from the church in the 1930s. In clearing the apse of the earlier chapel. it became evident that the holy rock on which the altar of the later chapel was built was not part of the bedrock.

Michael Avi-Yonah, “Heptapegon,” in The New Encyclopedia of Archaeological Excavations in the Holy Land, ed. Ephraim Stern, Ayelet Lewinzon-Gilboa, and J. Aviram (Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society & Carta, 1993), 614–15.

Renate Rosenthal and Malka Hershkovitz, “Tabgha,” Israel Exploration Journal 30 (1980): 207.