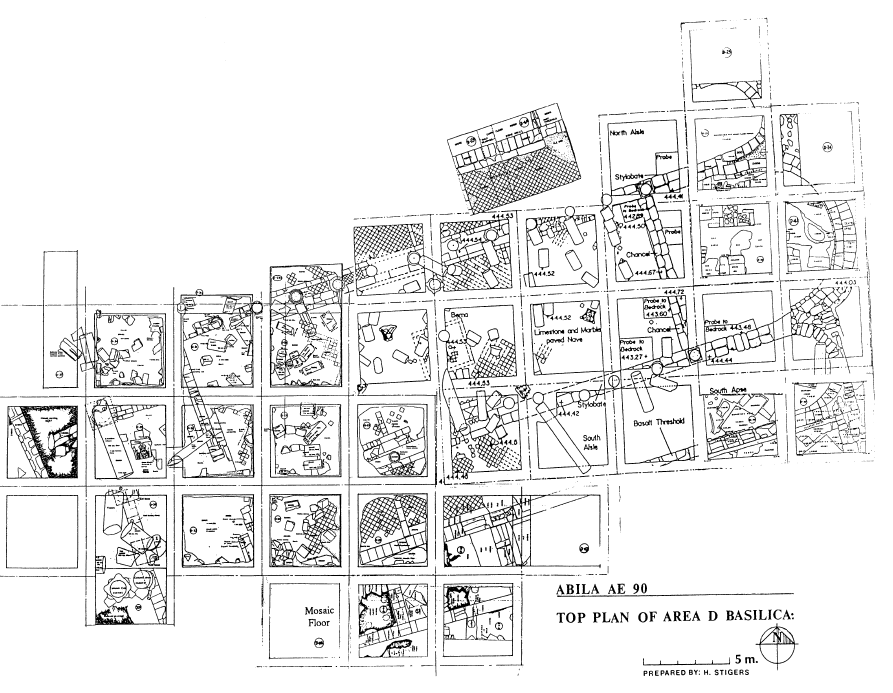

Excavation on the south tell, Umm el ‘Amad, has been conducted since 1984 and has revealed a 7th century A.D. triapsidal basilica (Area D), with dimensions 20,0 m by 41,0 m and with a row of 12 columns on each of the north and south stylobates which separated the nave (10,0 m wide) from the side aisles (each 5,0 m wide). The floor of the nave of the basilica was opus sectile, composed of diamond shaped lozenges, and in a special installation section the design is of circular and convex pavers of pink and black limestone and white marble. In auxiliary rooms on the south and in the porch and atrium sections of the basilica on the west the floor consisted of mosaics in geometric design, and in one room on the south (D 48) the mosaic consisted of a delicate design of flowers, a heart and a basket. On the west of the nave a large central basalt threshold was excavated (and an auxiliary threshold to its south), a threshold with pivots (lined with metal) for the large entrance doors to swing on, and nearby a large Euboean red marble column which had adorned the basilica. Excavation has also produced evidence that there were at least two entrances on each side of the basilica. Four large entrance columns (up to 1,00 m in diameter) were excavated at the entrance to the large porch west of the nave. Architectural and pottery evidence within the basilica point to earlier habitation here before the basilica was built – as early as the Middle or Early Bronze periods.

Harold Mare, “Abila of the Decapolis Excavations, June 30, 1991,” Syria (Paris, France) 70, no. 1/2 (1993): 209–12.

Across the nave just west of the central apse ran the stylobate foundation for the iconostasis; a portion of this stylobate with the cutting in the limestone for the installation of the altar screen was discovered.

Harold Mare et al., “The Abila Excavation – The Fourth Campaign at Abila of the Decapolis (1986) – A Preliminary Report,” Near East Archaeological Society Bulletin 28 (1987): 43.

In the narthex and the area to the West, the pottery in the surface and upper loci was Umayyad, showing an important Umayyad presence.

Harold Mare, “The 1988 Season of Excavation at Abila of the Decapolis,” Annual of the Department of Antiquities XXXV (1991): 212–13.

Additional investigation that the two smaller side apses were inscribed; perpendicular walls were found to inscribe each of these features, but the larger central apse was external or exposed. In contrast all three apses of the Area A basilica were exterior or exposed.

Mare, “The Sixth Campaign at Abila of the Decapolis,” 8–9.

At the seventh century AD basilica on the south tall, Umm al- ‘Amad, the excavation team uncovered, outside the south wall and toward its west end, more mosaic floor in squares to the west of those excavated in 1992; this mosaic was composed mainly of plain white tesserae, but in some cases the tesserae were of geometric design in red, black, etc. This additional evidence of flooring indicates that there was an extended series of service rooms along the church’s south wall.

Harold Mare, “The 1994 and 1995 Seasons of Excavation at Abila of the Decapolis,” Annual of the Department of Antiquities XL (1996): 264.

The excavators found attached to the north outside wall of the Area D church another apse structure, oriented east, no doubt part of a small chapel for special religious services.

W. Harold Mare, “The 1996 Season of Excavation at Abila of the Decapolis,” Annual of the Department of Antiquities XLI (1997): 306–8.