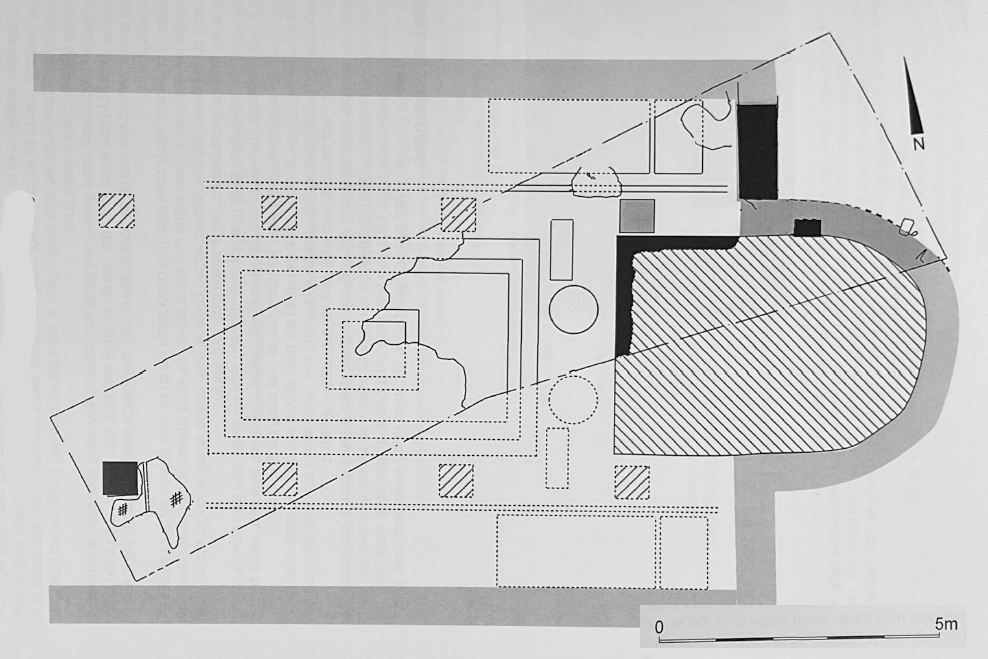

What we learn from a combination of the archaeological data and the inscriptions is that a village church, probably built in the sixth century. The settlement was apparently abandoned towards the end of the seventh century CE, clearly after the Arab occupation in 640 CE. The architectural evidence suggests that the site was soon reoccupied, and that the inhabitants made substantial changes in the buildings and the street. The continuity displayed in the pottery assemblages of the two strata suggests that the occupational gap between them was short. The church was significantly renovated, an event commemorated by the dedicatory inscription dated 785/6 CE. Four more architectural alterations were made in the church during this period.

Thus, by the end of the eighth or the early ninth century the church managed by an abbot, presumably the head of a small team of monks. The church, however, continued to serve the lay community, as is indicated not so much by its location in relation to the village, which obviously could not be changed, as by the mention of the ecclesiastical authority under which the church functioned, Metropolitan Anastasius of Tyre, as well as by the woman’s name inscribed in the pavement of the fourth phase.

The Commemoratorium de casis Dei, a document almost precisely contemporary with the dated inscription of Kh. el-Shubeika, reports on the number of clergy and monks in the churches and monasteries of the Holy Land, and we learn that in some churches (ecclesiae, distinguished from monasteria) in Galilee – one in Nazareth, another in Cana, both important pilgrimage places – there were no priests but only monks, twelve in Nazareth and the number lost in the more remote Cana. Evidently, by that time there was a lack of secular clergy and monks had to take the place of priests in order to continue the cult in surviving churches. No wonder, therefore, that the church of a humble village like Shubeika had to be served by monks.

Does this make it into a monastic church? Does it mean that there was a monastery there? The Commemoratorium, which lists many monasteria, mentions no such institution besides the ecclesiae held by monks in Nazareth and Cana. Those monks may well have lived in the village, like the spoudaioi of old, especially since – unlike the members of the renowned monasteries in and near Jerusalem – they were surely local men.

Leah Di Segni, “On the Contribution of Epigraphy to the Identification of Monastic Foundations.,” 188.

Evidence of a fire in the church may hint at the reason for the final abandonment of the church and the settlement in the tenth century CE. The findings of the survey indicate at least a partial reoccupation in the Crusader and Mamluk periods, while the site was ultimately used as a cemetery in the early twentieth century CE

Syon, “Excavations at Khirbet El-Shubeika 1991, 1993: The Church (in Hebrew),” *187.