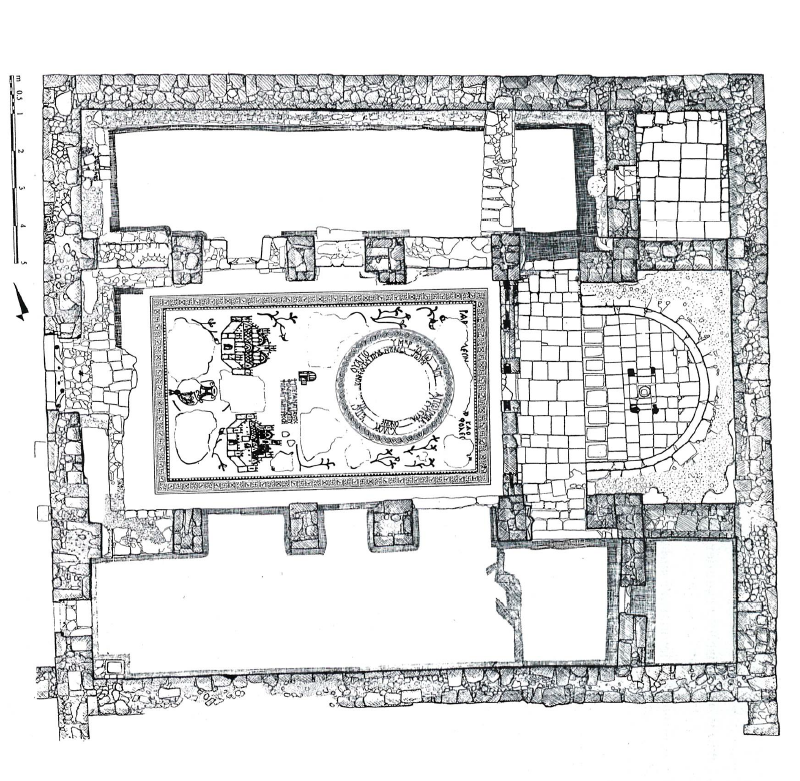

Originally, the church had the interior volume of a large hall rectangular, divided into three naves by two rows of heavy pillars. The space was progressively cut by the creation of two rooms at the top of the aisles, then the transformation of the north aisle in a separate chapel.

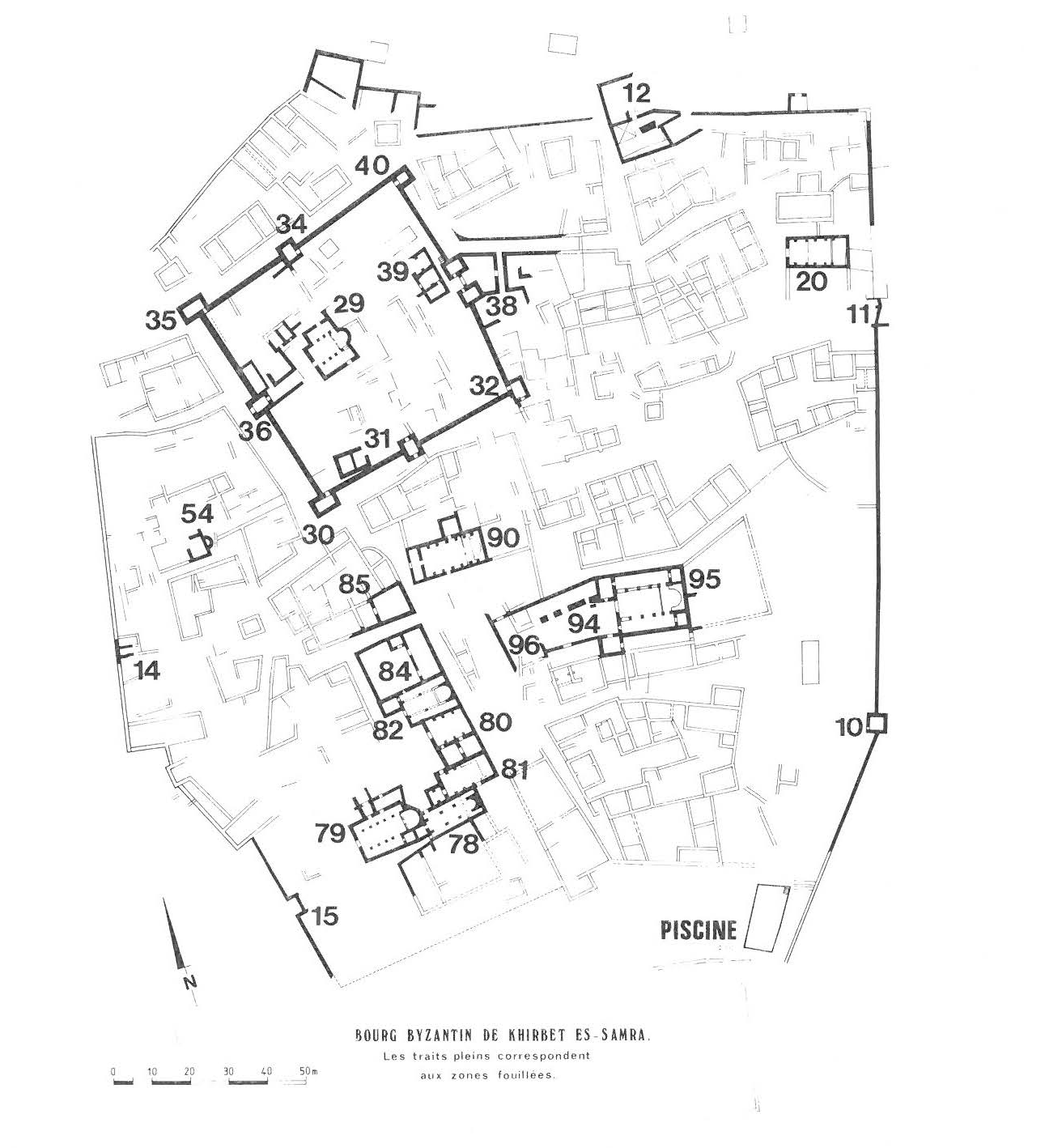

Jean-Baptiste Humbert and A. Desreumaux, “Huit Campagnes de Fouilles au ‘Khirbet Es-Samra’ (1981-1989),” Revue biblique 97, no. 2 (1990): 261.

The church was a basilica with three naves (17.25 x 14.70 m) which ended in a rectangular sanctuary inscribed between two side pieces. Contrary to other churches on the site, it was built of limestone. The building currently presents a rather complex state which is the result of several revisions.

It was originally accessed from the west by three doors which opened onto the central nave and the side aisles. The central door appears slightly offset to the north and its uprights show traces of reworking; the northern one was blocked at an unknown date.

The naves were divided into two rows of five pillars, which were obviously reinforced, and which supported arches. The nave ended in a rectangular sanctuary inscribed between two side rooms (3.50 x 2.50 m). Chancel screens were added to the side rooms in a later phase. Later, a room was fitted out in the northern aisle by the insertion of walls between the pillars of the first four spans; it was accessed from the central nave by a door located in the second bay.

Several annexes backed onto the church to the south and the west: to the west was a funerary vault which opened simultaneously on the north side of the church and on the outside; it was a rectangular room subdivided by an arcade and which contained six skeletons.

The sanctuary, which extended to the last span of the nave, was raised twice without its surface being modified. It was accessed by a doorway placed in the axis from the nave; the state of the stylobate no longer made it possible to specify if there were accesses from the aisles.

A two-step synthronon was added during a reworking in the rectangular sanctuary. Four cavities in the center of the sanctuary indicated still the location of the altar table which had four feet.

A reliquary, sealed by a marble disc in a coated cylindrical loculus, was placed between the altar supports. The loculus contained a limestone reliquary in the form of a small sarcophagus and a globular vase in glass The reliquary-sarcophagus had a semi-cylindrical lid with a cross at the ends, and a hole drilled in the center. The excavators supposed oil was infused into it, which was then collected in the globular vase – similar to a light bulb – by an orifice provided at the base of one of the walls of the tank, but N. Duval considers the globular vase as a second reliquary buried on the first.

Belatedly, masonry benches were added against the western facade and the northern wall of the church.

The floor of the church has known at least three states. The original plaster floor was replaced by a paving which reused architectural elements, some of which were registered. It was covered by a mosaic, polychrome in the central nave, and white in the side aisles.

The carpet of the nave, surrounded by a geometric border, with a kantharos at its western extremity, which succeeded, in the following registers, two representations of cities in an enclosure, an inscription, an open cage, and a circular medallion, whose border included the inscription of dedication. A third inscription ran along the border at the end orientate the pavement.

Most of the figured motifs of the mosaic have been destroyed and have not been repaired. Excavators attribute with likelihood of these destructions to iconoclasm: mutilations are very localized and therefore cannot be attributed to wear; only a few plant motifs remain stylized scattered on the carpet.

Anne Michel, Les Eglises d’Epoque Byzantine et Umayyade de La Jordanie V-VIII Siecle (Turnhout: Brepols, 2001), 197–99.

The mosaic of the central nave consists of a single carpet where the various decorative elements and the inscriptions in Greek were found in the field. We guess animal motifs destroyed by the iconoclasts; but two representations of cities surrounded by circular ramparts (1.50 m in diameter) have remained almost intact; they represent a theme, the city, little attested in the iconography on mosaics. Closer to the cancel, a large rosette 2.50 m in diameter bears a long inscription in two lines. It indicates the patronage of the church (Saint John the Baptist) and the date of the laying of the pavement through the name of the consecrating bishop, Theodore, known by the texts, as sitting at Bostra from 634. The repair of our building would therefore only have taken place shortly before the middle of the seventh century. However, because the dated mosaic covers an older, undated paving, it can be argued that the construction of the churches of Samra is contemporary with the economic and political development of Hauran, under Justinian (beginning of the 6th century).

Michele Piccirillo, “Ricerca storico-archeologica in Giordania II (1982).,” Liber Annuus 32 (1982): 499–500.