The building is a church of rectangular plan with three naves (internal dimensions; 13.10 x 8.30). Leaning against church 80, it was built later, slightly askew, with no angle being straight. The interior arrangement, pillars and pavements, tried to correct the irregularity of the plan by adopting an average orientation. Although the church is incompletely excavated, the distance between the pillars is 4.10m; this abnormally long span, combined with the precariousness of the construction of the pillars, forces us to design the entire upper part of the building in a material lighter than stone, that is to say in wood. It is not improbable that this sanctuary plan, different from the plans with an apse, also implies a different elevation.

Alain Desreumaux and Jean-Baptiste Humbert, “La Première Campagne de Fouilles à Kh. Es-Samra: 1981,” Annual of the Department of Antiquities of Jordan 26 (1982): 177.

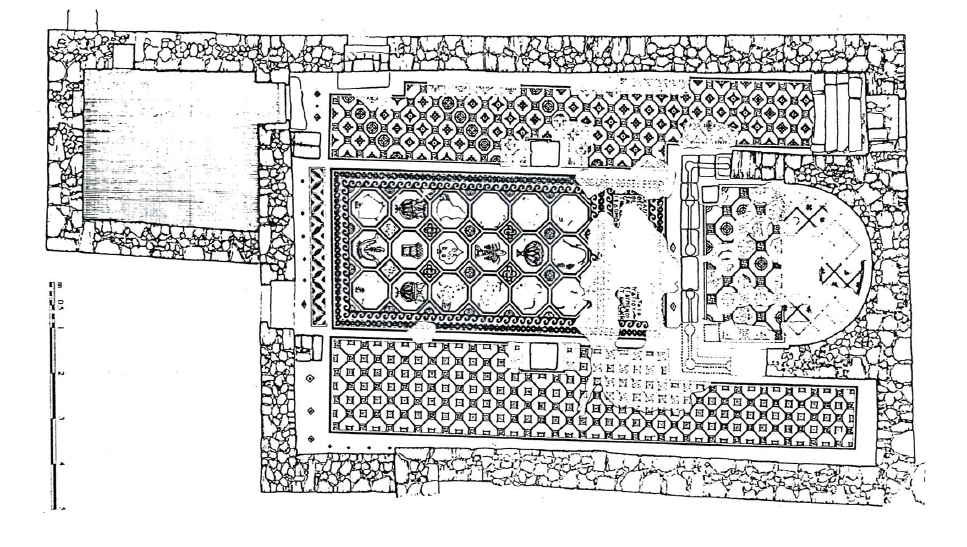

The church was a small basilica with three naves (11 x 15 m) which ended with an apse (opening 3.50 m; depth 1.90 m) inscribed between the extension of the aisles.

To the west, one entered it by a slope, slightly offset to the south, which opened onto the central nave. To the north, a second door placed near the western facade overlooked a courtyard; at the eastern end of the collateral north, a third door opened onto the street which ran alongside the group of buildings to which the church belonged. The naves were subdivided by two pillars, which were reinforced during a redesign, and which suppressed two series of two arches.

A roughly square room, the construction of which led to the shift of the western peak towards the south, leaned against the northern end of the facade. A niche was arranged in the north wall of the room.

Anne Michel, Les Eglises d’Epoque Byzantine et Umayyade de La Jordanie V-VIII Siecle (Turnhout: Brepols, 2001), 199–201.

Note the elegance of the initial construction: the roofing was only supported in the center by two square pillars measuring 0.60 m across; to the east, it was supported by uprights from the apse and to the west by two pillars leaning against the front wall. Thus the interior volume had to be spacious. But the reinforcement of the pillars in the center and the side walls of the apse demonstrates that the builder had made aesthetics prevail over solidity.

Michele Piccirillo, “Ricerca storico-archeologica in Giordania II (1982),” Liber Annuus 32 (1982): 499.

The sanctuary, raised by a step, extended into the central nave about 2.50 m in front of the apse. We accessed by a gate placed in the center of the barrier of chancel, including some fragments of the marble slabs were collected in the nave. The location of the altar, which left no trace material, can be restored in the apse, just by the rope, thanks to the design of the apsidal mosaic, or its location was reserved.

In the western corners of the sanctuary appeared two square embeddings (the second is rendered by symmetry on the published plans) which are not indicated in excavation reports; The photographs show on the north side a stone which could correspond to a supporting fragment of a secondary table, leaning against the chancel barrier.

Masonry benches were added along the north wall of the nave after the installation of the mosaic, of which they partially mask the drawing.

The walls of the church were covered with plaster, of which fragments remained on the north side.

The floor of the building was entirely paved with mosaics. The side aisles had geometric mosaic carpets, whose design carefully contoured the pillars of the nave, thus extending to the intercolumniations. The sanctuary was paved with two geometric panels.

Anne Michel, Les Eglises d’Epoque Byzantine et Umayyade de La Jordanie V-VIII Siecle (Turnhout: Brepols, 2001), 199–201.

The whole floor of the church seems to have been paved with mosaics. A large carpet in the central nave shows a field composed of octagons with ornate medallions of kantharos, cup, basket, and floral motifs which remained intact while the animal motifs were hammered out and repaired in disorder by iconoclasts. The border, very neat, is made up of braids and lines of posts. The central ring is separated from the cancel by a panel containing an almost heavily damaged Greek inscription.

Alain Desreumaux and Jean-Baptiste Humbert, “La Première Campagne de Fouilles à Kh. Es-Samra: 1981,” Annual of the Department of Antiquities of Jordan 26 (1982): 177.

The inscription preserved in a rectangular frame in front of the chancel’s stylobate made it possible to restore the date of laying of the mosaic floor, under the archiepiscopate of Theodore of Bosra, in 528 or 529. The mention of a hegumen constitutes a strong presumption in favor the interpretation of the complex to which the building belongs as a monastic ensemble.

By divine grace, under the Most Holy Archbishop Theodore was made the mosaic of Saint Theodore by the zeal of such a hegumen and … , … reader, John .. . At time of the 7 year of the indiction, the year (528 or 529?) of Province.

Anne Michel, Les Eglises d’Epoque Byzantine et Umayyade de La Jordanie V-VIII Siecle (Turnhout: Brepols, 2001), 199–201.