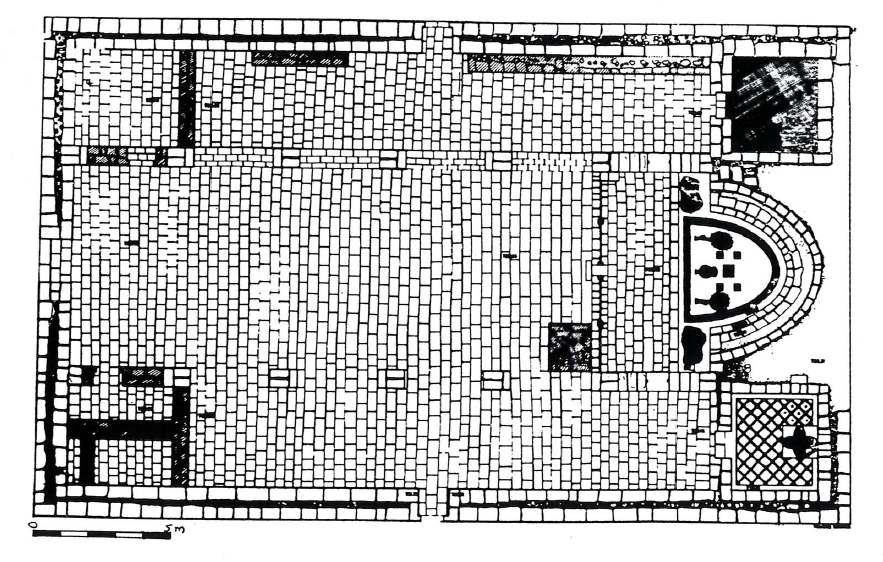

The main church of Hayyan el Mushref comprises an apse, where we recognize the remains of the altar framing a reliquary, flanked by two adjoining rooms, one of which houses the baptismal font and three naves whose roof was supported by two series of four pillars along the main nave. At the back of the church are two small rooms framing the entrance. Two side entrances were made in the middle of the north and south walls.

Square in plan, the atrium measures 15 x 17.70 m. The elements discovered in this sector highlight a phase of domestic occupation during the Umayyad and early Abbasid periods according to a process of tightening of space that the found on other sites.

Michele 1944-2008 Piccirillo, “Ricerca Storico-Archeologica in Giordania XVII – 1997,” Liber Annuus / Studium Biblicum Franciscanum 47 (1997): 495.

There is a bench along the north side as well as two small rooms on either side of the entrance. The apse was surrounded by two stepped tiers (synthronon).

The baptistry has two floors and the font rests on the recent level, which proves, given the style of the latter as well as the associated pottery, that it is at the end of the Byzantine period or the beginning of the Umayyad period. that the southern room was used as a baptistery.

The three naves are paved but the apse and the side rooms are decorated with mosaics. The apse is surrounded by a braid while two trees frame the altar in front of which is placed an amphora. The animal representations integrated into this composition were destroyed by the iconoclasts and were replaced by white tesserae. However, there are still some fragments belonging to a lion that are still recognizable. According to various indications, it seems that this pavement must be dated from the sixth century.

The potsherds found in all the areas studied date from the beginning of the Byzantine period to the Abbasid period. With the exception of a single sherd collected extramurally dating from the Mamluk period, no trace of later occupation has been revealed in this sector of the site.

Michele 1944-2008 Piccirillo, “Ricerca Storico-Archeologica in Giordania XV (1995),” Liber Annuus / Studium Biblicum Franciscanum 45 (1995): 519–20.

Numerous traces of liturgical installations are kept in the building, but the alterations they have known sometimes make their interpretation difficult. The sanctuary extended to the apse and to the last span of the central nave. Currently, chancel’s stylobate rests curiously on the paving of the sanctuary, at the same level as that of the nave; the traces of coating visible on the inner part of the stylobate on the north side and on the two steps placed on either side of the stylobate in front the central gate to the west indicate that it is probably from the primitive state of the barrier, whose stylobate was placed on the floor of the nave. The axial entry of the sanctuary was completed to the north and south by two lateral entrances for which we had not used the usual plates maintained by posts, but a system of posts placed on either side of the entrance, which held horizontal bars of wood or metal, of which superimposed symmetrical traces still remain in the pillars between which the fence was inserted.

A slightly protruding rectangular stone, evoking the loculi for relics of Saint Basil of Rihab, Saint George from Khirbat al-Mukhayyat or from the church of Deacon Thomas at ‘Uyun Musa was inserted into the pavement between the four mortises.

The masonry base of an ambo is still preserved in the south pavilion of the nave in front of the sanctuary. The recesses for plaques and chancel posts, which were originally provided for in the stylobate in front of access to the ambo, show that it is a development late.

The church had a secondary table with four legs in the northwest corner of the choir: on this side, two recesses remain in the chancel stylobate and a third notch is visible on the paving of the sanctuary.

Anne Michel, Les Eglises d’Epoque Byzantine et Umayyade de La Jordanie V-VIII Siecle (Turnhout: Brepols, 2001), 206–10.