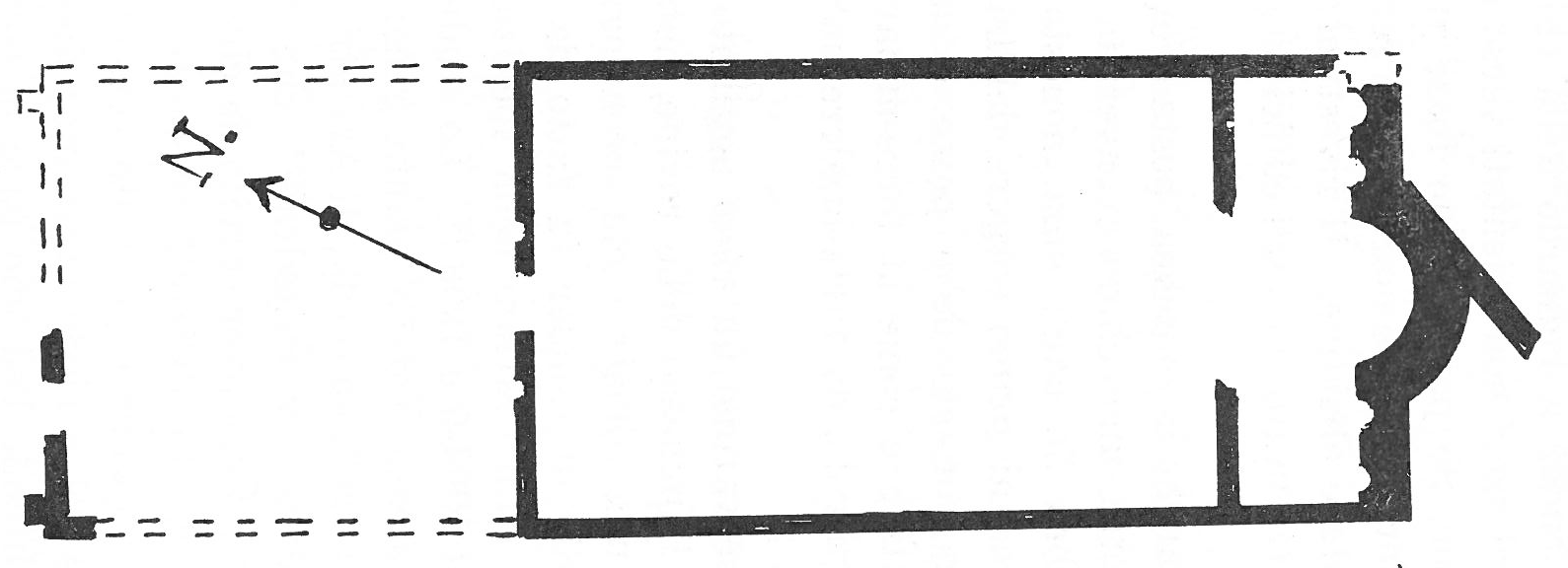

The cathedral lies in a south-east direction; its length, exclusive of the apse, is 137 feet 6 inches, its breadth, 7 3 feet inside. The west door is 9 feet 9 inches wide, and on the outside there is a niche or alcove 2 feet in diameter each side of the door ; the walls are 2 feet 8 inches thick. There is a north door, and remains exist of a wall 20 feet from the east wall, which appears to have divided the chancel, and may have formed the foundation of the iconostasis, the church being no doubt built for the Greek rite.

On each side of the main apse are two small apses or alcoves S feet 3 inches in diameter ; the central apse is 24 feet 9 inches in diameter, and 12 feet 6 inches to the back. This arrangement of five apses has not been found in any church west of Jordan.

The apse walls are very thick ; on the interior they are pitted with holes 1 ½ inches square and 1½ inches deep, like those in the walls of the baths already noticed. They may have been intended to facilitate the attachment of either a marble casing or of glazed tiles.

Two syenite pillars lie within the church, 11½ feet long, 1½ feet in diameter; and outside on the north-west lies a lintel-stone 13 feet long, 1 foot 10 inches high. There is a wall nearly parallel to the west wall of the church, 115 feet from it, with remains of a gate 8½ feet wide. The gate is, however, not on the central axis of the cathedral, and there is a difference of 1°3′ between the bearing of the west wall and this fragment of outer wall. The latter might belong to some sort of atrium; but it may, on the other hand, be part of a distinct building.

R. Conder, The Survey of Eastern Palestine: Memoirs of the Topography, Orography, Hydrography, Archaeology, Etc. (London: The Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund, 1889), 54-5.

Although the apse may have been utilized as part of a Christian building, and although the enclosing walls in front of it may have been the walls of a church, it is impossible to believe that the wall in question was originally built for any such purpose. The axis of the apse points a little east of south, so that its orientation is more that of a milzrab than of a presbyterium.

This ruin stands beside the stream, its rear wall rising directly from the bank; its width is about equal to that of one section of the great wall of the nymphaeum, and its apse is almost as wide as the central apse of that building, its niches are about the same dimensions as those of the nymphaeum, and it is certainly of about the same date as that great Roman building. It must therefore have been an edifice of very much the same character and appearance as the nymphaeum with the exception of the basin in front. It may easily have extended in either direction to form a plan of polygonal outline. It may have been part of a gymnasium or a portico with an exedra, and, indeed, it may have been joined to the nymphaeum, in which case a high massive wall may be conceived of as rising from the river for a distance of nearly 200 meters, with a colonnade in front opening upon the plataea between the river and the junction of the two colonnaded avenues.

Howard Crosby Butler and Enno Littmann, Syria: Publications of the Princeton University Archaeological Expeditions to Syria in 1904-1905 and 1909., vol. 2:A (Leyden: E.J. Brill, 1919), 59.

Recorded and planned by the Palestine Exploration Fund survey in 1881, the only known photograph dates to the visit of Warren in 1867. The plan reveals a basilica measuring 41.9 x 22.3m. To the northwest a further wall may have belonged to an atrium with an off-axis entrance. In 1867 the apse, which was external, stood as high as three courses of the semi-dome, together with a section of the aisle end-wall on the east side. The apse was flanked by pairs of shell niches in two tiers, making a total of eight. According to Conder, these niches are ‘small apses or alcoves’. The word ‘niche’ here reflects the evidence of a Palestine Exploration Fund photograph, that these are set into the body of the wall, and should not properly appear in the ground-plan. The church did not therefore have five apses, as Conder describes it.

The building seems to have disappeared before 1900.

Alastair Northedge, Studies on Roman and Islamic Amman: The Excavations of Mrs. C-M Bennett and Other Investigations, British Academy Monographs in Archaeology ; No. 3 (Oxford: published for the British Institute in Amman for Archaeology and History by Oxford University Press, 1992), 59.