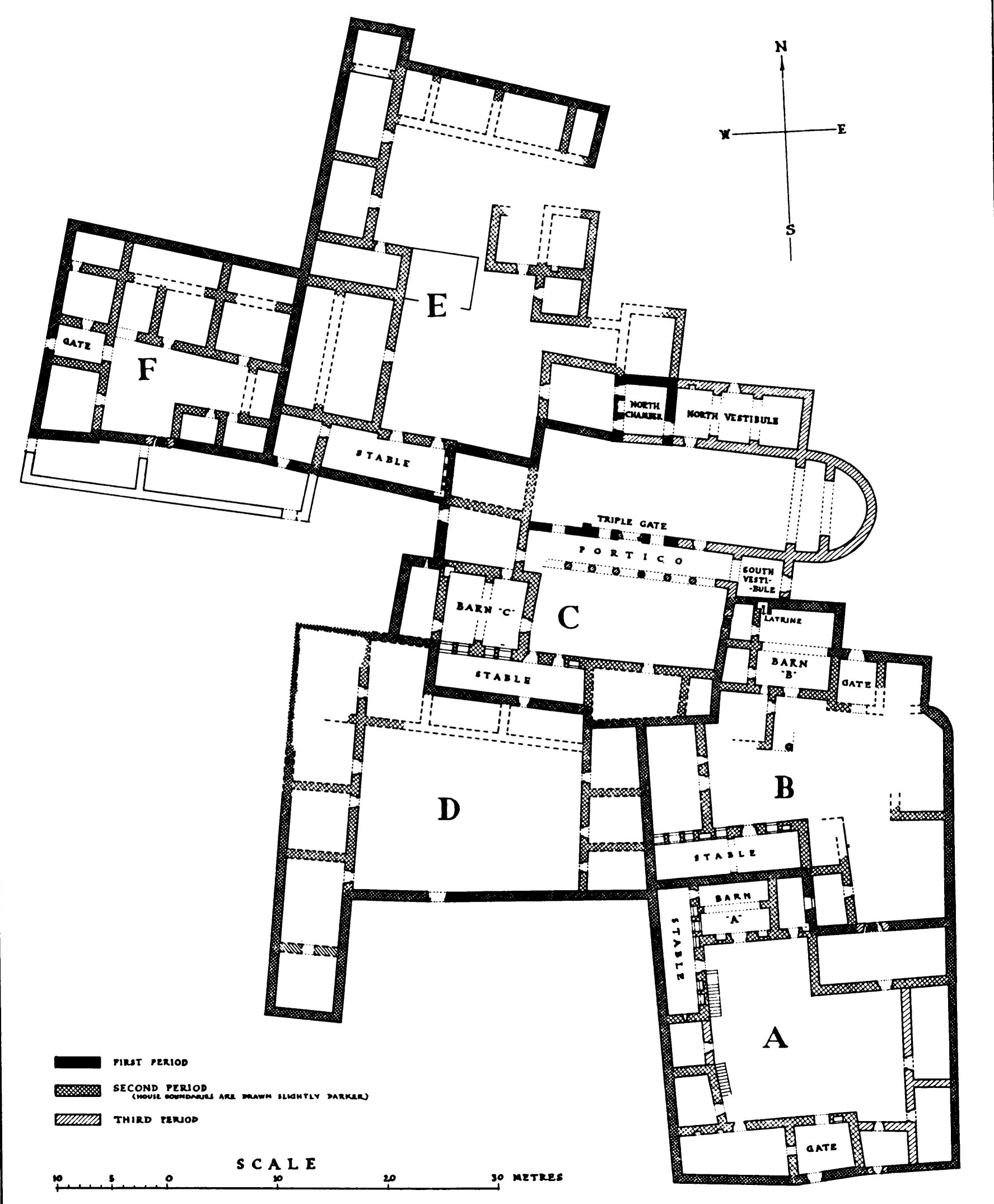

The Julianos Church is part of an insula comprising six distinct houses (A to F on th eplan) placed together quite unsystematically, except that the various walls are approximately at right-angles to one another. Each individual house is more-or-less a simple rectangle, albeit with excrescences, but notably more organised in plan than the whole insula, which has no organized plan at all; its irregular outline resulting from the apparently haphazard contiguity of the six houses.

Corbett, G. U. S., “Investigations at ‘Julianos Church’ at Umm El Jimal,” Papers of the British School at Rome 25 (1957): 45.

House C has the same essential elements as A and B; namely a courtyard, a barn, a stable and a latrine in a corner of the barn (pl. XL VIII). The barn is on the west and the stable is on the south side of the courtyard. The east side is closed by House B, while on the north side of the court we find the south wall of the church nave. In general it appears that the church was built as an extension of the house; making use of some of its walls and superseding others. It overlaps the north-east corner of the house but leaves untouched the stable, the barn and the courtyard.

Corbett, G. U. S., “Investigations at ‘Julianos Church’ at Umm El Jimal,” Papers of the British School at Rome 25 (1957): 50.

It appears that the nave of the church was formed by the re-modelling of walls belonging to two earlier buildings. The first of these, the Triple Gate, was adapted to form an entrance to the nave and part of a colonnade along its south side. The second set of pre-existing walls to be incorporated in the nave are its west wall and the western extremity of its north wall.

These walls were part of House C and it follows that, before being incorporated in the church, the Triple Gate already formed part of House C. While the western half of the church is made up of earlier walls re-modelled, the eastern half seems all to have been built at one time and for the special purpose of the church.

Corbett, G. U. S., “Investigations at ‘Julianos Church’ at Umm El Jimal,” Papers of the British School at Rome 25 (1957): 54.

The church was a single nave building (10.00 x 32.00 m) ending with a projecting apse (diameter 8.50 m, depth 7.00 m). It was accessed from the south by a columned patio opening onto the nave by a triple door (which belonged to an older building), and to the north by a vestibule.

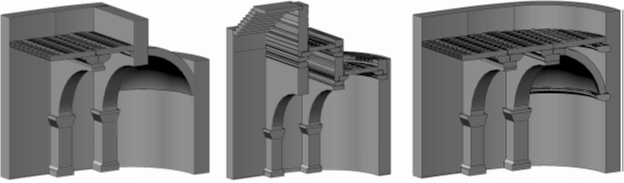

Proposals for the superstructure of the church differ according to the authors. Butler proposed covering the nave and the bedside of the building by a system of slabs resting on arches. Corbett restores a frame on the nave and a covering of stone beams divided into two different levels in the apse and the choir bay preceding. More recently, an engineering-based model reconstructs the building’s manufacturing process by considering structural systems, construction processes, and sustainability measures. It yields three hypothetical roofing systems that depart from the “classical template.”

Rama Al Rabady and Shaher Rababeh, “Engineering the Reconstruction of Hawrān’s Ecclesiae during Late Antiquity: Case of Julianos Church in Umm El-Jimal, Jordan,” Heritage Science 10, no. 1 (2022): 14.

A basalt step (14 cm high), fragments chancel posts in Proconnese marble and pieces of plates were collected in the eastern part of the nave from the 1956 excavations. Their disparate character led Corbett to conclude that the chancel screen had been repaired at least once. A three-step synthronon showing traces of plaster and having an axial staircase was placed in the apse.

The coated column drum found in the part south of the nave, just east of the chancel, could correspond has a table stand. A second chancel stylobate was unearthed in the western part of the nave, at the height of the western pillar of the triple door. It featured weak recesses dimensions (10 x 10 cm approx.), which indicated, according to Corbett, a wooden or metal fence interrupted by an axial po1tillon with two leaves which had left traces.

Surveys have made it possible to recognize, in the west section of the nave, the bed of a first mosaic floor, which was then covered with a plaster floor.

On a lintel broken into two fragments, found on the floor from the Church of Julianos:

This is the memorial of Julianos, compelled to a long sleep, for which Agathos (his) father built it, pouring a tear, very close to the public cemetery of the (people) of Christ. In the end the best people will have to sing forever publicly his praises, as being of his living faithful (son) of Agathos, (the) priest, (and) much loved, age twelve years old. The year 239 (344 AD).

According to Butler, the inscription was originally to be placed above the southern central portal of the church and would match the original dedication, but Corbett rightly attributes it to a reused stone from the neighboring cemetery.

Anne Michel, Les Eglises d’Epoque Byzantine et Umayyade de La Jordanie V-VIII Siecle (Turnhout: Brepols, 2001), 169.