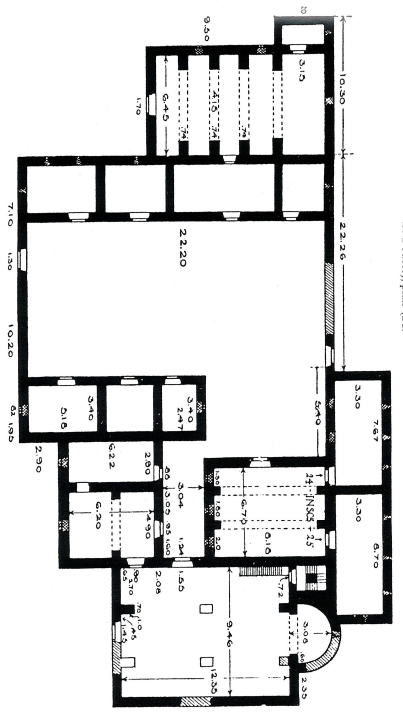

Examination of the church, the monastery complex against the north wall of the church, and the church tower built against the north-east side of the church and its apse, indicates that these represent successive stages of work on the site. The church is of well-cut basalt; the original building was a simple rectangle with an apse but no tower or other appendages, and in quality sufficiently good to be of a 5th or 6th century date as Butler suggests, rather than the 7th century date mentioned in the foundation inscription in the monastery.

Subsequently, the complex of buildings to the north of the church was added. The walls of these structures are of more roughly cut basalt than the church, and they uniformly break bond at those points where they abut the north wall of the church and the apse.

The late date of 624-5 A.D. seems appropriate for the poor building quality of the monastery. In general, the ground-plan published by Butler is correct as far as the church itself is concerned, but some hesitation must be expressed regarding the extent of the complex to the north as described by Butler; those rooms which may be considered with certainty as appendages of the church were perhaps fewer than he suggested. Furthermore, monastery walls which abut the apse and the tower break bond, contrary to the indications of Butler’s plan.

The third stage of building in the complex is represented by the addition of the tower which is built resting on the surviving north side of the church’s apse, and on the north-east corner of the church; on the east side, the tower rests on top of a wall of the monastery. This method of constructing the tower caused a considerable amount of disturbance to the walls beneath it. This is marked in the apse, most of which was pulled down either before or at the time that the tower was added. The chancel arch preceding the apse has been closed off by a wall which Butler does not mention, but whose construction is apparently contemporary with the reconstruction in the ruined apse that was necessary to support the new tower. As to the base of the tower, the means by which it is inserted into the pre-existing church and monastery is such that it was necessary to make the lower part of the tower solid; its entrance is on the west, approached from within the church.

Butler noticed a staircase of corbels approaching this entrance, but they have now vanished. He also states that the staircase inside the tower is crude and attributable to the early Islamic period, while the tower itself he regarded as early Christian. There is no evidence to suggest that the tower and the staircase are of different dates. It seems reasonable in fact to attribute the entire tower and the walling off of the destroyed apse to the Islamic period. It is therefore to be assumed that the well-built tower is a minaret, and that the church was transformed into a mosque, although there is no mihrab. Nevertheless, there is a space in the centre of the south wall of the church, very precisely set, with much fallen stone inside the church in front of it. If it was a mihrab perhaps built on the site of an earlier door to the church, nothing remains of it, but in an area where inscribed, decorated or otherwise distinguished stones are removed, this would not be unusual. The problem of dating the change of the church into a mosque is more difficult.

Geoffrey King, “Preliminary Report on a Survey of Byzantine and Islamic Sites in Jordan 1980,” Annual of the Department of Antiquities of Jordan 26 (1982): 89–90

King concludes from careful analysis of the architecture that the church was converted into a mosque. Like the church at Umm es-Surab, a tower was built to the north of the apse, a wall without a door was built blocking off the apse from the chancel, and the apse was dismantled. In the middle of the south wall is a space where a mirab might once have been, but whether there ever was one is an open question. While the presence in the area of Umayyad and Mamluk sherds might suggest that the conversion could have taken place in either period, the fact that minaret towers were not built in the Umayyad period indicates that the conversion took place in the Mamluk period.

Robert Schick, The Christian Communities of Palestine from Byzantine to Islamic Rule: A Historical and Archaeological Study, Studies in Late Antiquity and Early Islam (Princeton, N.J: Darwin Press, 1995), 448.