The church edifice was of medium size; the ecclesiastical residences beside it were built about an open court, or cloister, in the middle of which was a large cistern, arched over, and roofed with stone slabs. The group possibly constituted a small monastery, but the residential buildings are hardly large enough to have housed more than a small number of monastics, and it seems more probable that they were built to accommodate the regular priests of a parish church.

The church is one of the most interesting of all those that we found in the Southern Hauran, a true basilica of three aisles separated by two rows of five columns each, and having an upper story, or gallery, over the side aisles. The chancel arch is still in situ though closed up by a later wall built, probably, when the nave was converted into a mosque. Two columns of the north aisle are standing at opposite ends of the nave, with architraves above them. These columns are of simple late Doric style. The north wall preserves a corbel course on the level of the architraves, and the broken slabs which lie in the aisle show that a stone floor was installed between the colonnade and the wall. The columns of the gallery, of the Ionic order and lighter than the columns of the main colonnade, are lying in the middle of the nave. Corbels in the east wall, on either side of the chancel arch, show the height of the upper colonnade, and the north wall bears remnants of a second corbel course with a weighting wall, or parapet, above it. The tower which stands above the prothesis was altered by being provided with stairs in later, Moslem, times. In the process of this change the prothesis was filled up.

The apse was deep-set. The diaconicum on its south side had two stories. At the west end of the north aisle was a square tower that contained stairs leading to the gallery.

The lower order is composed of a late variety of Doric columns with a well proportioned, but perfectly straight, echinus, and a base like an inverted capital with a heavier echinus, and a circular band next to the plinth. The upper order, a rigid imitation of the Ionic column, has a base consisting of a narrow torus below a fillet and a shallow cavetto, an unfluted shaft, and a capital which, though well executed, has only the general form of the Ionic.

Outside the main portal, on either hand, is a colymbion, or basin for holy water, corbelled into the wall. The form of these basins is a simple half-cylinder hollowed out at the top.

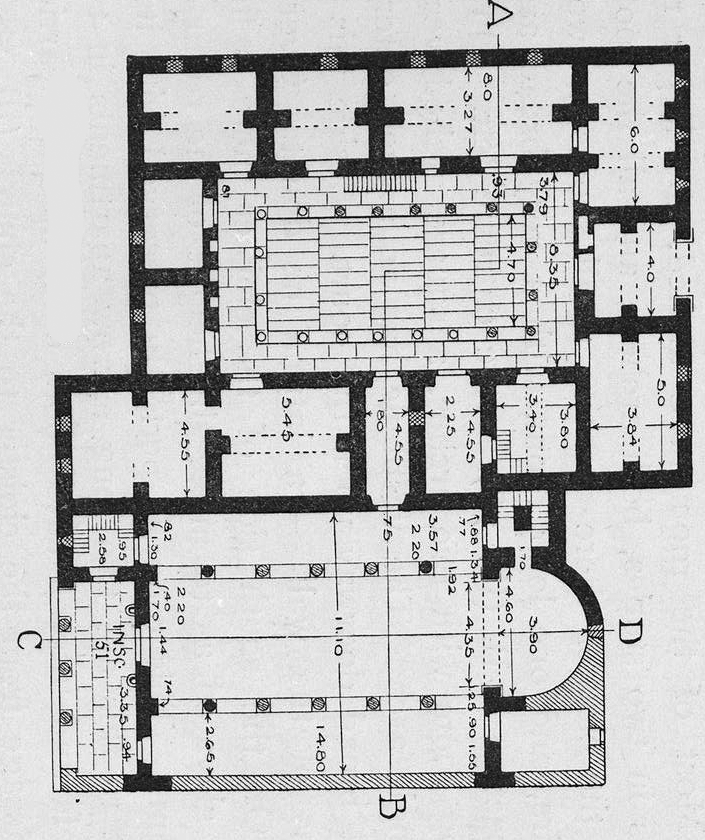

The buildings north of the church compose a rectangle, 18 m. by 24 m., about a cloister, 8.40 m by 13.80 m.; these buildings are quite well preserved, except at the northwestern corner. Most of the rooms are arched, the larger rooms being in one story, the smaller ones in two stories, both arched; and all the roofs are on one level.

The cistern itself was spanned by four transverse arches carrying slabs which formed a pavement for the open part of the court. The cistern was very well made, and lined with thick plaster, much of which is still in place. Some fragments of a smaller order of columns and of the panels of a parapet, or railing, give the data for the reconstruction of the upper colonnade.

Howard Crosby Butler and Enno Littmann, Syria: Publications of the Princeton University Archaeological Expeditions to Syria in 1904-1905 and 1909, vol. 2:A (Leyden: E.J. Brill, 1919), 95–98.

The church of Sergius and Bacchus is dated by a foundation inscription over the main west door to the year 384(?) of the Province (489 A.D.). Re-examination of the church and the monastery on the north side of the church indicates that again Butler’s descriptions and his plan are generally correct, but with serious omissions and misinterpretations. The most important of these are the following:

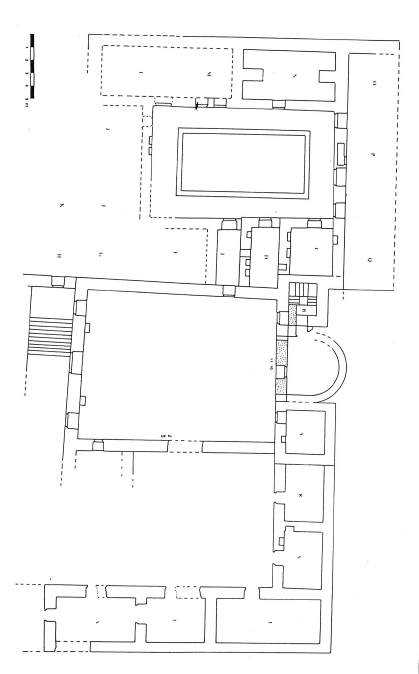

- Whereas Butler shows the church with a complex identified as a monastery on the north side, there are also wall traces of rooms to the south whose precise chronological relationship to the church remains a matter of doubt.

- The walled-up apse, the destruction of the apse and the addition of the tower should all be attributed to the Islamic period. As at Sama, the church tower appears to be a minaret.

- There is evidence that plain mosaics formed part of the decoration of the interior walls of the church. There is also evidence of polychrome stone and glass mosaics. A small fragment of polished marble was found a few meters west of the church.

Geoffrey King, “Preliminary Report on a Survey of Byzantine and Islamic Sites in Jordan 1980,” Annual of the Department of Antiquities of Jordan 26 (1982): 90.

The church was a basilica with three naves (12.40 x 20.00 m approximately) flanked to the north and south by several outbuildings organized around courtyards. To the west, there was a portico with columns opening by three gates on the church. All three had lintels decorated with crosses, which were inscribed in a circle for the two side doors, and which framed an inscription in a dovetail cartouche (see below) for that of the center. According to King, the tower accessible from the north aisle of the church and placed in front of the north door which Butler restores correspond more to a room than to a tower and would be the result of a later revision.

The naves of the church were divided into two rows of Doric columns, exceptional layout in the Hauran. Galleries with Ionic columns, whose slab floor was supported by stone corbels, still visible in the walls of the aisles, were located above the aisles. Butler posited a covering of stone beams above the side aisles and a frame above the central nave.

The church originally ended with an apse inscribed between two adjoining rooms. Currently, the apse (opening 5.50 m x depth 3.70 m) is closed. It is flanked to the north by a square room which served as a foundation for a tower.

King’s study allowed us to recognize an adjoining piece at the church at the western end of the south wall; it was apparently contemporary with the construction of the building and the author suggests that it allowed access in the South structures.

Two stone stoups protruded from the wall of the church, outside, on either side of the central door.

Polychrome tesserae which probably belonged in the mosaic of the apse were collected. Remains of plaster bearing the imprint of large tesserae have been observed on the western wall of the church, attesting to the existence of parietal mosaics. A fragment of smooth marble collected in front the building suggests that the walls were also covered of veneers. Traces of stucco painted red were observed on architectural fragments lying in the nave.

An inscription in a dovetail stamp was engraved on the lintel of the central door of the facade west of the church:

Lord, protect us. Ameras and Cyr, sons of Ulpianos [have completed with the help] of God (?) this memorial of Saint Sergius and Saint Bacchus, the 25th (of the month of) Gorpiaios, the year 384 (September 12, 489).

Anne Michel, Les Eglises d’Epoque Byzantine et Umayyade de La Jordanie V-VIII Siecle (Turnhout: Brepols, 2001), 187–89.