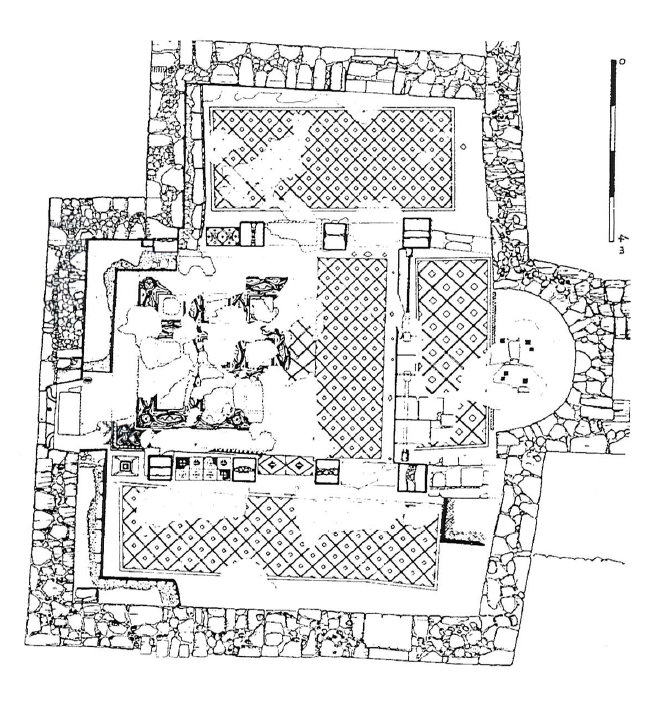

In the hope of touching structures from the Roman period in the heart of the castellum, a sounding was carried out in the apsidal building spotted last year, at the intersection of the diagonals of the fort; we hoped to clear one of the administrative buildings of the complex. We discovered that the apse belonged to a church which we named “29”. It is preceded by a courtyard which communicates directly by an island street with the western postern of the castellum.

Since the church uses walls belonging to previous buildings, church “29” presents a plan wider than long. Unfortunately, the mosaic pavement was almost completely damaged both by iconoclasts and by a workshop in the 8th century. No inscription has survived from it. As in the other sanctuaries, added plaster benches rest on the mosaic. The choir testifies to a minimal displacement of the altar; the most notable item is the presence of a niche in the apse, but too low to have been used for an exhibition for the faithful. It will have been rather a more noble place behind the altar to place an object concerning the liturgy.

By way of conclusion, we recall that the Arab historian Yaqut recounts that the disused strategic works of the Limes had been used from the seventh century by monastic communities. It is not impossible then, that the castellum (60 x 65 m) sheltered within its walls, in the heart of Samra, a monastery. And if a hegumen is mentioned on an inscription in the church “82”, it is perhaps simply that of the castellum/monastery, as one of the ecclesiastical authorities of the locality.

Michele Piccirillo, “Ricerca storico-archeologica in Giordania VI (1986),” Liber Annuus 36 (1986): 360.

The church was a small basilica with three naves of squat proposals (12.60 x 13.50 m), ending in a protruding semi-circular apse (opening 3.00 m approximately, depth 1.70 m) which had a small semicircular axial niche in its wall.

To the west, it was accessed from a small square, by a door slightly offset towards the south in relation to the axis of the nave; two other doors opened onto the aisles of the church.

The naves were subdivided by two rows of four pillars supporting arcades; the insertion of the building between pre-existing buildings led to the shortening of the north aisle.

The sanctuary, which included the apse and the last bay of the nave, was delimited by an awkwardly inserted chancel screen; it was accessed by an axial gate.

Traces of embedding in the mosaic indicated the location of the altar in the apse. It was a table with four supports, probably redone and slightly moved, as indicated by two other similar recesses in the immediate vicinity of first.

The line of stones that ran along the curve of the apse could correspond to the core of a synthronon.

Masonry and coated benches were added during a repair against the western and southern walls of the church.

The building was entirely paved with mosaics, already heavily damaged at the time of the excavation. The central nave was adorned with two mosaic carpets. The first, to the west, surrounded by a guilloche border, composed a field of squares separated by geometric interlacing, with figured representations, systematically destroyed then repaired by reusing the same tesserae. The second panel, in front of the chancel, consisted of a simple oblique grid like those of the aisles and that of the part of the sanctuary preceding the apse.

Anne Michel, Les Eglises d’Epoque Byzantine et Umayyade de La Jordanie V-VIII Siecle (Turnhout: Brepols, 2001), 194–95.