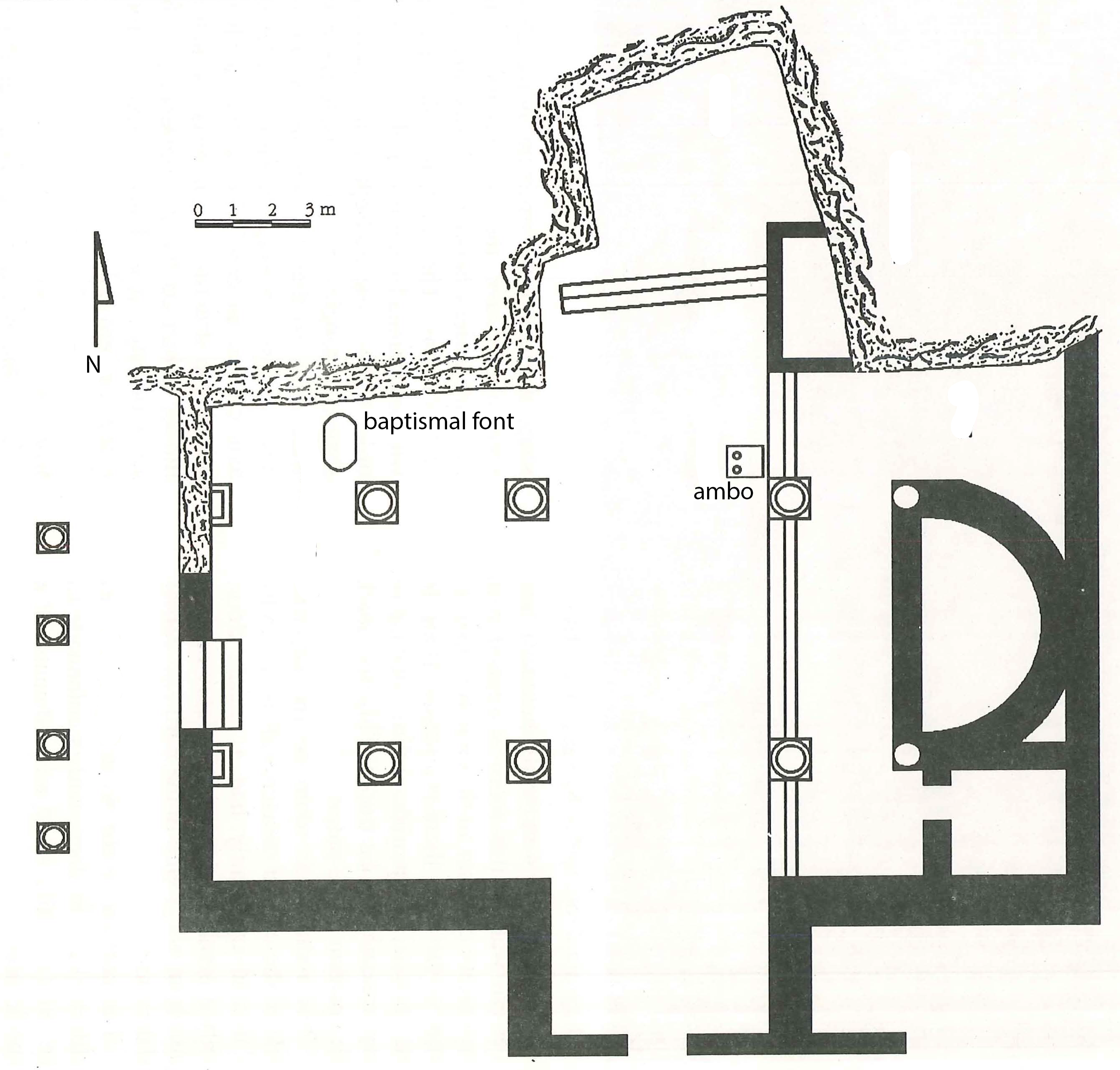

The church consists of a rectangular hall laid out in an east/west direction, with a semicircular apse to the east. There is an entrance to the west which is not in the center of the western wall. West of the entrance is a narthex or porch. To the north is a cave and, to the south, a rectangular room which may have led to a second entrance into the church.

The main hall is divided into three parts by two rows of three columns standing on square bases. The columns are of a conglomerate stone and were topped with Corinthian capitals. Both the columns and the capitals were obviously reused from an earlier Roman monument. The hall of the church measures ca. 14.8 m by 12.5 m, while its central part (the nave) is about 6.8 m wide and the two side aisles are about 3 m wide. Normally in such churches the spacing between the columns is equal, but in this case it is not. The first two columns at the east (in front of the cave) are 6.8 m apart while the distance between the columns to the west is 4 m.

The eastern part of tile church was separated by a chancel screen running the whole width of the church and attached to the two eastern columns. The chancel, which is about 3.4 m deep, is divided into three sections.

The central part has colored marble tiles, while the side ones have the remains of mosaic floors. The semicircular apse has a diameter of about 5. 8 m.

South of the apse is a room which was probably a sacristy. It measures 3 m by 3.3 m. and had a mosaic floor. North of the apse, and at about 4.3 m east of the chancel screen, there is a plastered surface which seems to be covering the wall of another cave which was left unexcavated due to the presence of a modem terrace and staircase.

In the western part of the northern aisle there is a baptismal font. The location of this font is unique as fonts are normally located either in apsidal spaces or towards the ends of rooms. It consists of an oval cut into the floor and has some plaster remains within. A fragment of mosaic remains just north of it. The font measures 1.5 m by 0.8 m. A similar oval font is found in a church in Kursi and it is dated to A.D. 585 by an inscription in the mosaic floor.

The cave to the north has four niches, one in its eastern wall, another in the northern one, while the remaining two are in the western wall. The northern niche of this wall is broad, shallow and taller than the others, whereas the southern niche, the largest of the four, has what may be the remains of a sarcophagus. The cave measures about 8 m east/west and 8.7 m north/south. About 2.2 m inside the cave, there are two steps going down to the main part of the cave.

Within the cave, there is a room built of rectangularly cut stone blocks and measur ing about 2 m by 4 m (walls included). The western wall of this room is aligned with the eastern columns in the church proper. In front of the cave, there is a mosaic floor. In the mosaic, a squarish outline, devoid of any tesserae, can be traced. This may mark the position of the pulpit.

The rectangular room on the opposite side of the church measures about 3. 7 m by 6 m and apparently had a mosaic floor. Only a small section of this richly-colored pavement was found in the northeast comer of the room.

The narthex to the west is about 13 m wide and 2.8 m deep, with a colonnade to the west. Again, there are remnants of a mosaic floor.

At first glance, the church appears to be of the basilica type with the standard division into nave with · two aisles and an apse to the east. On closer examination, however, we see more than a basilica since a cross shape is given to the structure by the alignment of the cave, the southern room, and the wide spaces between the first and second columns. The intercolumnar spacing was determined by the width of the cave. in order to have the transept as a uniformly shaped rectangle, the walls inside the cave were built, so that the structure would be more or less symmetrical. This north/south axis creates an emphasis on the northern part of the structure, an emphasis which is further enhanced by the presence of the ambo or pulpit as well as the baptismal font in the northern aisle.

Mosaics

The church’s nave, chancel, and apse were paved with marble, but the rest of the church, including the narthex, was paved with mosaics, only fragments of which now remain. Most of the mosaics were made of large tesserae, mainly in white, with some being red, yellow, or blue. No shapes could be seen in the mosaic of the sacristy, while those in the chancel area and the northern aisle (in front of the cave and adjacent to the baptismal font) have the form of flowers.

The mosaic south of the cave includes a Greek cross in the northwest comer.

Prior to the construction of the church, the cave may have been the tomb of a revered person or another type of holy place since it was incorporated into the church. The area in front of the cave was also used before the church was built, as in the south-eastern part of the church, remains of an earlier north/south wall cut into bedrock and having plaster on its eastern face were found. Associated with this wall is a thick plastered surface aligned with it, lying north of the apse, and apparently covering another cave which is at present unexcavated.

The inscription mentioning Herakles is still at the site, but the St. George inscription has disappeared. The inscription mentioning the Roman god Herakles and a second inscription which perhaps refers to the Roman emperor Trajan lead to speculation as to whether an earlier monument, perhaps dedicated to Herakles, existed at or near this site. Byzantine churches were often built above Roman temples and here there is extensive reuse of Roman architectural elements.

Pierre M. Bikai, May Sha’er, and Brian Fitzgerald, “The Byzantine Church at Darat Al-Funun,” Annual of the Department of Antiquities 38 (1994): 402-406.