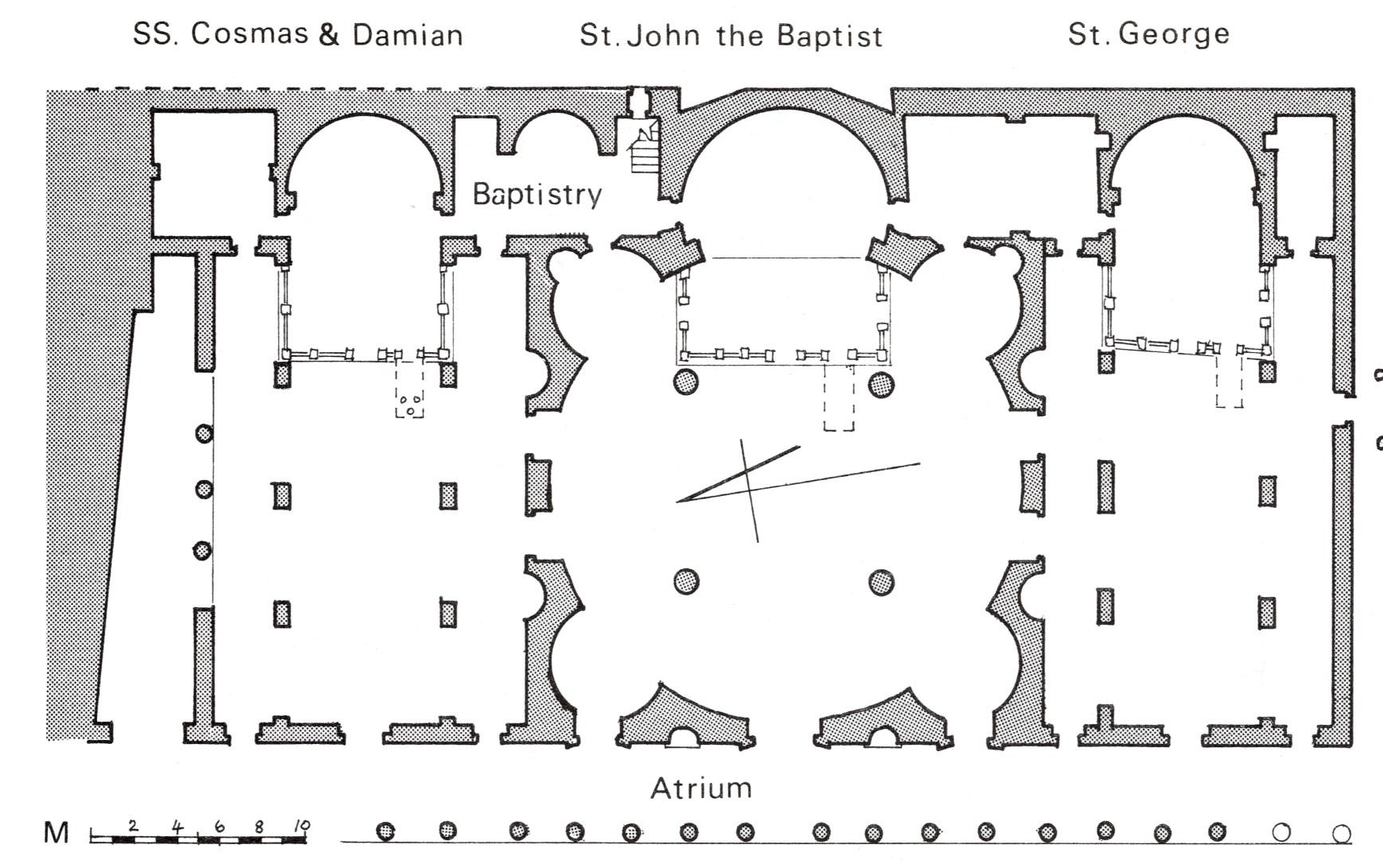

These three churches lie about 150 m. west-northwest of the atrium of St. Theodore’s. The group consists of a “central” church flanked by two parecclesia, basilicas in which the arcades were carried not on columns but on piers. All three buildings opened on a common atrium. Inscriptions show that they were completed between 529 and 533 A. D. and were dedicated respectively to St. John the Baptist, St. George, and SS. Cosmas and Damian.

The atrium was rhomboidal in plan, much longer from north to south than from east to west. On the east side there was a colonnade of 14 Corinthian columns on a low stylobate. The columns, many of which were obviously displaced, vary in diameter, and the capitals found in this area are very miscellaneous in character. The collonade was paved with red and white mosaics of which little remains; enough is preserved, however, to show that there were different patterns in front of each church. The interior of the atrium was paved with stone slabs.

St. John the Baptist’s church.

According to an inscription in front of the chancel steps the central church was built in the episcopate of Bishop Paul from offerings made by Theodore, the foster-son of Thomas. It was dedicated to St. John the Baptist, and was roofed and decorated with mosaics in 531 A. D.

In plan this church consists of a circle inscribed in a square, with four horseshoe exedrae in the four corners, a horseshoe apse at the east end, and outer niches on either side of the lateral entrances. On the north side of the apse there was a baptistery which reached to the apse of St. Cosmas’, and on the south a long chamber which extended up to the apse of St. George’s. The church is simply a reduced edition of the cathedral at Bostra which was built some twenty years earlier, 512-513 A. D. The Bostra cathedral measures approximately 50 by 38 m.; St. John’s 29.50 by 23.80 m. The proportions are accordingly the same, but the number of doors, niches and internal supports have been reduced in the smaller church.

Inside the church there were rows of plug-holes which showed that the walls were originally revetted with stone or marble.

The chancel had been completely dismantled; there were scanty remains of a colored marble pavement, but no trace of altar or ambo, except one of the supports of the latter in the nave, was found; the tiers of seats round the apse had disappeared entirely. That these seats had once existed was proved by the absence of plug-holes for a stone or marble revetment round the lower courses. Three crosses were carved in relief on the east wall, but they must have been hidden before the removal of the seats.

The room north of the apse is arranged in its present form as a baptistery, but originally it was planned as a chapel with a chancel screen running from north to south, the two small flanking chambers being paved with mosaics and lit by windows in the east wall. When it was converted into a baptistery, a font was let into the apse, the screen broken, and a flight of steps built in the south chamber over the mosaics, leading out to a bridge across the street east of this group of buildings through a door where a window had been. The patterned floor was stone and marble. A great deal of late pottery, like that we found in the atrium rooms, and a small hoard of about 30 Umayyad coins of the first half of the eighth century was found there.

The room south of the apse was paved with common mosaics and the northeast quarter of it was raised by one step above the rest of the floor. The door leading from it to the apse of St. George’s was blocked at an early date, but the room still communicated with St. John’s both through the apse and the southeast exedra, and with St. George’s through the north aisle. It was presumably a sacristy serving both churches. The wall of St. John’s apse is not bonded into the back wall of this room.

St. George’s church.

According to an inscription in front of the chancel this church was roofed, paved with mosaics and decorated in 529 A. D.; it was therefore the first of the group to be finished. It was dedicated to St. George by “one whose name the Lord knows,” and the dedication tempts us to identify the unknown benefactor with Georgia, the wife of the paramonarius Theodore, whose portrait occurs with her husband’s in St. Cosmas’ church.

It was a basilica, but, as in the north parecclesion and as nowhere else in Gerasa, the arches which carried the roof rested on piers instead of columns. Originally there were three piers and two responds on each side of the nave, but in St. George’s they were drastically reconstructed at some time or other. The ground shelved away to the south and west, and the foundations were not good enough to bear the weight laid on them. From this resulted the sinking of the pavement in the north aisle with disastrous results to the mosaics there, the fall of the arcade piers, and perhaps the collapse outwards of the south wall. The blocks used in the reconstruction of the northeast pier included grooved stones from some chancel screen.

There were three doors at the west end and a porch on the south side, all with plain door jambs. Two small Corinthian columns which were found near the middle door at the west may conceivably have come from a west window.

The side walls of the apse were stilted in plan, but the chancel steps were not set out square with the west wall of the church. Since the mosaic inscription in front of the chancel runs on a line with the steps, their present arrangement must be an original feature of the plan. The main mosaic field in the nave, on the other hand, is on the same line as the west wall, the difference between the two being made up in the border.

Two steps led into the chancel which included the first bay of the nave, and a third step rose. in line with the responds of the arcades. The screen sockets showed that there were three openings, one in the middle of the west side, one. in front of the ambo, and one on the south side. A doorway which once led from the higher part of the chancel to the chamber east of the north aisle was blocked by an extension of the. tier of seats round the apse. There was a slab of revetment in position against it. The floor was paved with different colored marble setts, and immediately in front of the bishop’s throne there was a stone reliquary with a single cavity on the top, apparently in its original position. A second reliquary of the same type, presumably from one of the other churches, was found near by.

Fragments of fine black marble screen posts and slabs were found in the same neighborhood. Pieces of this same screen had been used to patch the mosaics, and others were found in St. John’s. It would seem that St. George’s continued in use after the two other churches were stripped. Of the three, St. George’s alone has a tier of seats round the apse, and as the curve of these seats was evidently cut for a bigger semicircle it looks as if St. George’s chancel was restored at the expense of St. John’s.

The chamber at the east end of the south aisle, presumably another sacristy, had a mosaic floor with a fret border and a recess on the north side.

SS. Cosmas and Damian church.

All together there are six mosaic inscriptions on the floor of St. Cosmas’. A single line on the surround immediately below the chancel step gives the dedication and the date, which was early in 533 A.D. A long ten-line inscription below this refers to Bishop Paul and the founder, whose name Theodore the mosaicist regarded as a translation of John (the Baptist). Named portraits of Theodore, further described as the paramonarius, and his wife Georgia are on either side of this inscription, and three panels in the top line of the main nave field contain the names of donors or helpers, among them Dagistheus, one of Justinian’s less successful generals.

The church is a basilica and in its main features reproduces faithfully the plan of St. George’s. It was built against the hillside, and the dependent rooms on the north side were in part cut out of the rock. In consequence it is much better preserved than its sister church. Furthermore, by some happy chance, the mosaics here escaped mutilation. Wear and tear has led to their disappearance in the northwest part of the church, but elsewhere they have suffered very little.

St. Cosmas’ differs from St. George’s only in details. It is about 1 m. wider from north to south, a difference mostly due to the width of the south aisle, which is about 0.75 m wider than the north. St. Cosmas’ is also slightly wider at the east end than at the west. The chancel steps are square with the nave, and the ambo was of a different type, resting on three little columns. The most important new feature was an exedra on the north side. Opposite the two middle bays of the nave arcade the north wall is replaced by an open colonnade of three small columns and two antae with molded bases, all notched to hold a screen. The bases and the stump of one drum were found in place, and near them a notched Corinthian capital and some broken architrave blocks. This exedra was originally approached through an arch at the west end. Its north side was cut out of the rock to a height of 2 m. Above this the masonry wall is set back a little to give space for a gutter cut in the rock and now leading to a bath which was constructed at a later date in the northeast corner, when the whole of this part was converted to some secular use and much pulled about, the colonnade being then walled up. It is difficult, consequently, to be certain about the primitive arrangement. The pavement was made of coarse red and white mosaics. Like the lateral chambers in the Cathedral and St. Theodore’s, this exedra may have served as a narthex.

The chancel was of the same dimensions as the chancel in St. George’s, but it was quite empty; there were no remains of seats or altar, and the pavement had been wholly removed, leaving bare the bedding, which was of limestone chips. A stone from the roof with glass mosaics still adhering to it showed how the roof had been decorated. There were the usual plug-holes for a stone revetment in the walls, whereas the walls of the nave were plastered and painted. The northeast chamber contained a number of plastered blocks with inscriptions painted on them, but all trace of the pavement had disappeared.

Carl H. Kraeling, Gerasa, City of the Decapolis; an Account Embodying the Record of a Joint Excavation Conducted by Yale University and the British School of Archaeology in Jerusalem (1928-1930), and Yale University and the American Schools of Oriental Research (1930-1931, 1933-1934) (New Haven, Conn.: American Schools of Oriental Research, 1938), 241-247.