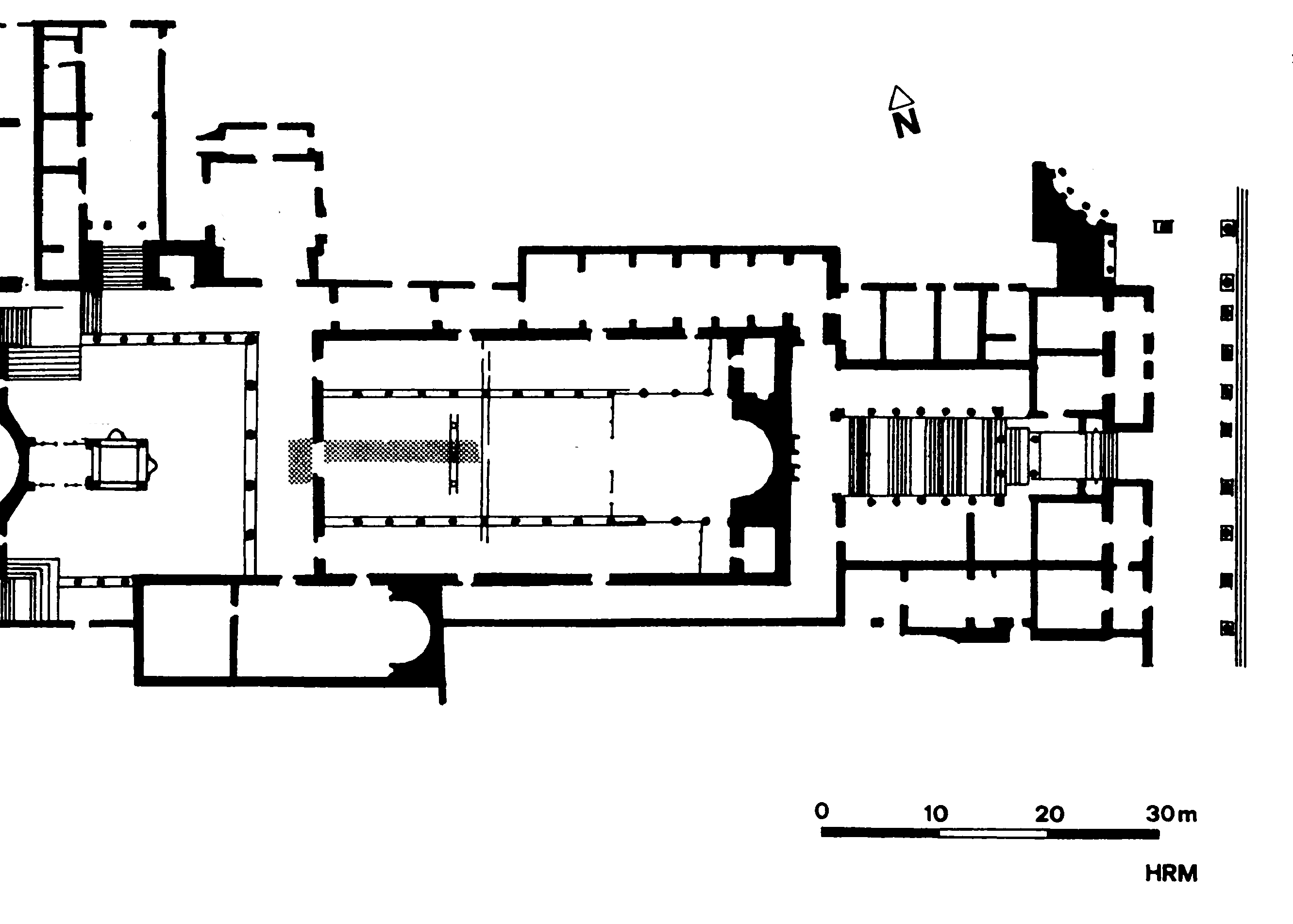

What proved to be the entrance to the principal Christian buildings in Gerasa abuts on the Nymphaeum on the west side of the Cardo. The facade of the portico which formed the eastern entrance to the buildings round the fountain was carried by eight Corinthian columns on square pedestals. Behind the colonnade there is an elaborate doorway with two rooms on either side. The portico was evidently designed as the entrance hall to an independent complex of buildings separated from the Artemis buildings by the Nymphaeum and a narrow roadway. Since the central portion of the Propylaea in front of the Artemis precincts was finished about 150 A.D. and the Nymphaeum in 191 A.D., the erection of our portico must fall between these limits. The floor of the portico was originally paved with red and white mosaics laid in a simple lattice pattern.

The moldings of the central doorway belong to the same period as the portico, namely, to the second half of the second century, but it has been questioned whether the door was originally erected in its present position or placed there later when the entrance was reconstructed by the Christians. The flight of steps, on the other hand, to which the doorway led has certainly been reconstructed. The walls on either side of the steps are built in the same style as the walls of the Cathedral.

At the top of the steps in front of the east wall of the Cathedral there was a terrace leading to the passages along the north and south aisles. In the middle of this terrace, we found the remains of a shrine built against the east end of the church. The center was formed by a finely carved shell-headed niche, perhaps of Hadrian’s time. On the band beneath the shell the names Michael, Holy Mary, Gabriel were painted in red letters. The shrine cannot be earlier than the second quarter of the fifth century, when the cult of the Virgin first became popular. The Archangels, Michael and Gabriel, occur together frequently as the guardians of towers, doorways or entrances to churches, in just such a position as the one they occupy here. Immediately in front and on either side of the shrine the terrace is paved with rough blocks, in contrast to the smooth paving of the wings and the side passages to which they lead.

The Fountain Court was also the atrium of the Cathedral. The miraculous fountain stood in the middle and originally there were porticoes on all four sides, but, as the fame of the fountain spread, other buildings were added and the plan of the atrium was radically changed. The portico on the east side rested on six columns with octagonal bases and Corinthian capitals belonging to the end of the second century. The three lower porticoes were in the Ionic order, but comparatively little of them remains. The whole portico at the west end and at least two of the columns on the north and south sides were swept away when St. Theodore’s church was built at the end of the fifth century.

The pavement of the east walk is divided into six panels filled with octagons and squares in a pattern found elsewhere at Gerasa, the octagons of red limestone and the squares of white. In the north walk the paving is lighter, and, being set flush with the top of the bottom step of a flight of stairs coming down from the north, is no doubt a late addition. In a sounding under the apse of St. Theodore’s we found a small patch of early mosaic on the level where the west walk would have run. It is probable that all four porticoes were thus originally paved with mosaics. The middle of the court is paved with rectangular slabs which were laid before St. Theodore’s was built. They include two inscriptions and some molded stones, and wherever we looked under the slabs they appeared to rest directly on the rock.

The structure of the fountain itself was also modified considerably in the course of time. Originally it was a square tank built on three sides of fine pink limestone blocks with a molded cornice and base, and with slight pilasters on the corners and in the middle, dividing these faces into panels; the fourth, west, side was composed of ill-fitting ceiling coffers. Basins stood against the east and the north sides. When St. Theodore’s was built, the east wall of the apse was connected with the fountain by two arches which supported a vault, a stone seat was placed against the apse wall for the officiating priest or bishop, and the space under the arches was railed off like the chancel of a church. At about the same time, a vault of some kind was raised over the tank itself, but the materials are too scanty to permit its restoration. Finally, the railings were removed, and, in the seventh century perhaps, some clumsy walls ·with steps on either side were built in their place.

The basilical cathedral (2.4 x 40.0 m) has suffered grievously from depredations in ancient and modern times. Three columns of the colonnade which divided the nave from the south aisle are still standing. The lower courses of the main walls are also in position. These, together with the paving of the aisles and the foundations of the chancel screen, are practically all that now remains of what was once the most splendidly appointed church in Gerasa.

There were three doors leading into the church from the atrium. On the north side there were originally four doors, but the two easterly ones were later closed up. On the south side two doors led into the passage, a third was opened when the chapel at the southwest corner was added, and there are traces of a fourth which was blocked at this time.

The aisles were separated from the nave by colonnades each of twelve columns with Corinthian capitals, and responds only at the east end; all were evidently taken from the same building.

In the nave the paving has disappeared almost entirely except where the ambo stood. Of the ambo itself nothing remains. In the aisles, on the other hand, the paving, which is of heavy blocks of hard pink stone, is nearly intact. It stops short of the side walls, perhaps to allow for a border below the revetment. A few centimeters from the edge there is a row of square sockets where the legs of benches may have stood.

The chancel was confined to the central part of the church and stretched down to the fourth column from the east, almost a third of the nave being enclosed within the rails. One step led from the nave to the railed area, and another step from this to the floor of the semicircular apse. As was invariably the case at Gerasa, the ambo stood just south of the central entrance to the chancel, and was approached directly from it.

Hardly any trace of the seats round the apse and none of the altar remain. A small reliquary of the sarcophagus type was found in the southeast chamber.

The passage along the north side of the church falls into two sections. The west half, corresponding to the six west bays of the church, was spanned by three arches carried on massive piers; there was a door at the west end leading into the Fountain Court. The east section was twice as wide and was spanned by six arches springing from smaller and lower piers, one of which was built in front of an earlier door into the chamber at the east end of the north aisle; the north wall of this section has collapsed almost completely. There are horizontal slots in the sides of the piers, which presumably carried benches. Both sections are paved with heavy slabs which now slope down towards the east, and the jointing of the paving stones to the east section corroborates the other evidence that the widening of this part was a later modification. The widened eastern portion of this passage we are disposed to regard as the women’s narthex.

The passage on the south side, which would have served as the men’s narthex, does not now run farther west than the fourth bay of the church, where it is blocked by the east wall of the chapel. The paving is like that in the north passage and the room was closed by a door in line with the most easterly bay of the church.

The southwest chapel, which blocked the passage on the south side, spans the four west bays of the Cathedral as well as the east alley of the atrium, and had a separate forecourt extending farther west. The walls are of poor masonry compared with the Cathedral, and the door which communicates between the two was very roughly made. A door with old molded jambs led into the Fountain Court alley, and a third door into the west court. On the outermost border just in front of the chancel screen there are the fragmentary remains of an inscription, “a memorial of the repose of those who have contributed … and of Mary.” The chancel floor was paved with stone and marble slabs set in a pattern. Four sockets of the supports of the ciborium and, at the north end of the screen, three out of four sockets belonging to a table were still in position.

So far as one can judge from the mosaics, in particular from the type of the floral border, this chapel belongs to the second quarter of the. sixth century. It is certainly much later than the Cathedral.

Carl H. Kraeling, Gerasa, City of the Decapolis; an Account Embodying the Record of a Joint Excavation Conducted by Yale University and the British School of Archaeology in Jerusalem (1928-1930), and Yale University and the American Schools of Oriental Research (1930-1931, 1933-1934) (New Haven, Conn.: American Schools of Oriental Research, 1938), 202-217.