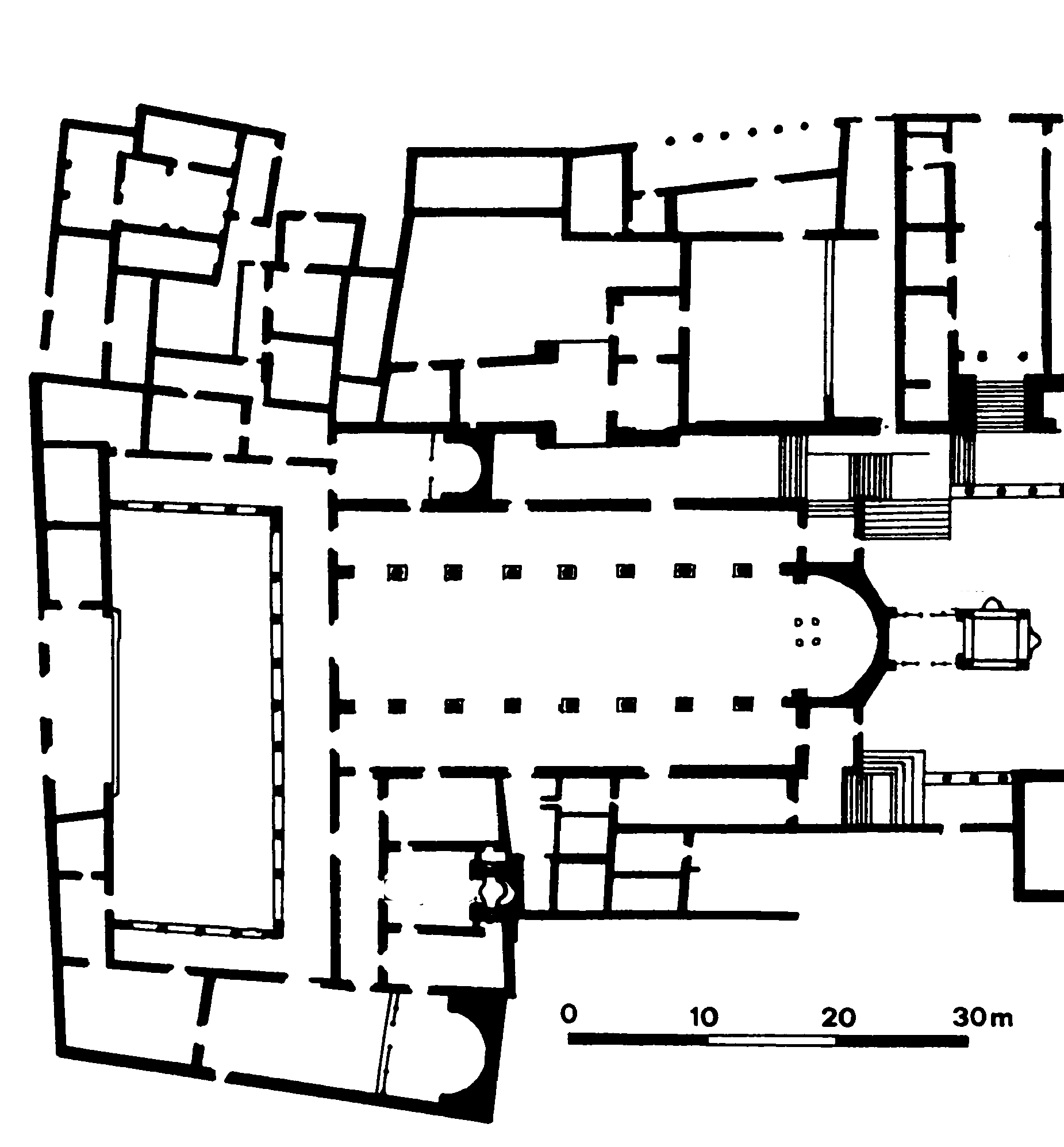

The atrium was rhomboid in shape; the open space in the middle measured about 30 m. from north to south and a little over 10 m. from east to west. The west wall of the atrium was built of very massive stones, many of them dangerously dislocated by earthquake shocks. It ran alongside a small street which formed the western limit of the complex. A triple entrance only approximately in the center of this wall led into an entrance hall which was paved with mosaics, and from this three long steps descended into the open court. The court had porticoes on three sides only, the north, east and south; the columns in the. porticoes had Ionic capitals. Some of the columns may have been moved here from the Fountain Court when it was reconstructed. The floors of the porticoes were paved in mosaics with a simple lattice pattern. At the north end the floor of the. open court in the center was formed by the leveled rock, in the south half it was paved with stone.

On each side of the steps leading into the court there were two large niches, which seem originally to have been built as thrones or seats. One of them was later converted into a water trough. West of the court on either side of the entrance hall there were three rooms, two of them paved with mosaics. At the north end there were three more rooms partly cut out of the rock, and at the south a large chapel with a separate forecourt. Some of the rooms had been remodeled in later days to serve as stables, others had been occupied by squatters. They contained several pots in earthenware and bronze, and a few early Arab coins.

The basilica of St. Theodore’s was only a little smaller than the Cathedral’s, and on either side of the aisles toward the west end there were subsidiary buildings and similar long lateral chambers to the east. The nave ended in an external polygonal apse and the roof was supported on two arcades, each of seven columns with two responds. These were the principal new features in the ground plan of the later church.

The floor of St. Theodore’s is more than 5 m. above the level of the Fountain Court, and at the east end it is laid upon a filling which is held up by walls under the apse, the aisles and the lateral chambers. The two side walls (under the aisles and the lateral chambers) stand on what appears to have. been the line of the original west wall of the lower court. The apse wall, on the other hand, and the flights of steps which communicate between the two levels project some distance into the court.

The church had twelve doors, three at the west end, three on the north, four on the south, and two at the east end of the aisles. Two other Gerasa. churches, the Prophets’ and the Synagogue, had doors at the east end of the aisles. In St. Theodore’s, nine of the doors, all in fact except those which opened into inner adjoining rooms, had molded jambs from earlier buildings.

The internal supports of the roof rested on two arcades, each of seven columns with two responds. The columns vary in height from about 6.55 m. to 6.75 m. and were composed each of three or four drums. The drums have masons’ marks cut on the section at both ends. 20 The capitals are not later than the beginning of the third century. The distance on the centers measures 4.38 m. as compared with 2.75 m. in the Cathedral, and several voussoirs from the arches above them were found in the debris, one still decorated with mosaics.

The floors of the nave and aisles were paved with slabs of different colored stone and marble, laid in patterns, but very little of the pavement was left.

In plan the chancel was very like the chancel of the Cathedral before it was enlarged. It extended into the nave over rather more than one bay and a half. It was raised one step above the floor of the nave. The pavement had disappeared, likewise the seats round the apse, but the bottom supports of the ciborium, the altar and the socketed foundations of the screen were still in place. The ambo stood as usual just south of the central and only entrance to the chancel. One of the small pillars which divided the panels of the screen was found lying broken under the column nearest the ambo.

The chapel at the west end of the north aisle had three doors, one on the south side opening into the basilica and two at the west end, one leading into the atrium and the other into a room adjoining it. Like the chapel at the southwest of the Cathedral it had a nave and a chancel railed off by a screen. The floor of the nave was covered with a fine mosaic, an elaborate geometrical pattern in which yellow predominates, perhaps contemporary with the basilica.

On the south side of the basilica a doorway close to the west end opened into a passage which ran alongside the east walk of the atrium to a small church or chapel at the southwest corner of the whole complex. The wall between this passage and the atrium as a continuation of the west wall of the church and was built at the same time. A doorway ornamented by conched niches on either side led from the atrium into the passage. The passage was originally paved with mosaics and the walls revetted like. those in the basilica.

On the east side of the passage there were three rooms which communicated with each other and with the two churches north and south. The central of these rooms was apparently converted into a baptistery when St. Theodore’s was built. It was previously a small chapel on a trefoil plan, a so-called cella tricliora. The chapel, perhaps a small martyrium, so far as we can reconstruct it, ended originally in a semicircular apse with minute apses (“absidioles” one would prefer to call them) less than a meter wide on either side. Two small niches were made between the shoulders of the apse and the side walls of the main building which widened a little towards the east. The floor of this chapel was nearly a foot below the present floor which is on the same level as the floors of all the adjoining buildings. When the chapel was converted into a baptistery, the floor of the nave was raised to the level of the passage floor and paved with slabs of stone and marble like the floor in St. Theodore’s; an oval-shaped font with three curious bins behind it was constructed on the original level in the central apse, and short flights of steps leading down into the font were built in the two side apses; these flights of steps communicated with the two side chambers.

To the east three rooms paved with mosaics may have formed part of a house for priests and deacons which, according to the Testanientum, should stand behind the baptistery. At the south end of the atrium there was another small church or chapel with a small independent atrium to the west. This church was of the ” hall ” type and the walls diverged towards the east end like the walls in the baptistery. It had five doors, one on the south, one on the west, and three. on the north side. In one of the last the two metal pivots on which the doors had turned were still in position. The. floor was paved like St. Theodore’s with slabs of limestone and marble. The sockets of the screen and part of the seats round the apse were still left.

Carl H. Kraeling, Gerasa, City of the Decapolis; an Account Embodying the Record of a Joint Excavation Conducted by Yale University and the British School of Archaeology in Jerusalem (1928-1930), and Yale University and the American Schools of Oriental Research (1930-1931, 1933-1934) (New Haven