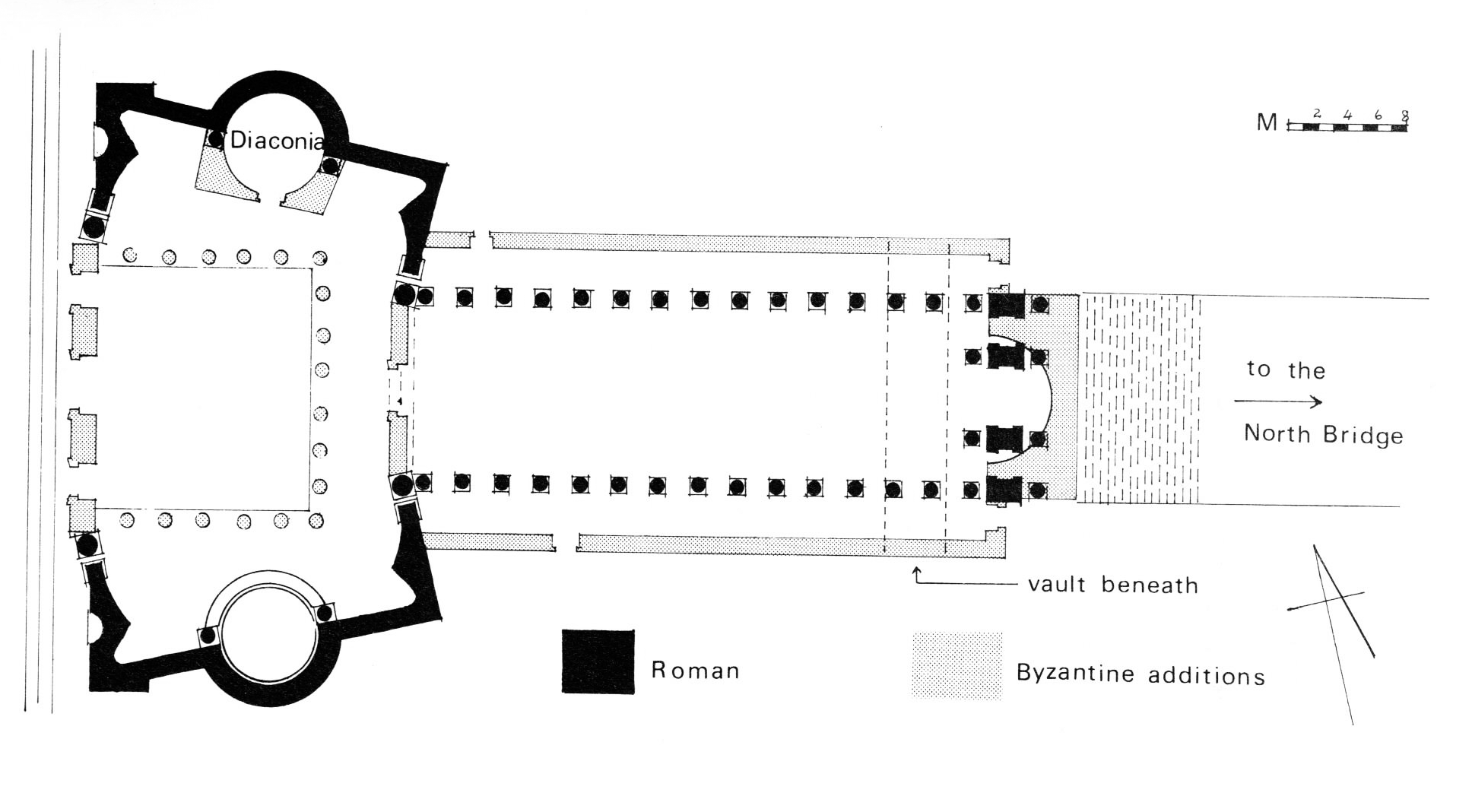

The atrium and the basilica to which it led are built inside two classical forecourts through which a great ceremonial paved road ran from the north bridge to the Propylaea. The atrium was laid out inside the enclosing walls of the west forecourt; in the east forecourt the colonnades on either side of the ceremonial way were taken over as they stood to divide the nave of the basilica from the aisles; other portions of the earlier structure were incorporated in the east and west walls.

The classical west court, in which the atrium of the church was built, was set out in plan as an isosceles trapezium. The two towering columns at the east end are some 11 m. apart; the corresponding pair on the west side are more than 19 m. from each other. The roadway from the eastern colonnaded court therefore widened gradually as it neared the street, thus giving a wider view of the Propylaea beyond. The fan-shaped center of this court was apparently on the same level as the main street, but on either side of it, between the lofty columns, there were raised terraces with flights of steps leading up to them and semicircular exedrae in the middle of the outer walls behind. This court was remodeled in Christian times, partly to form an atrium of the conventional pattern, and partly to provide additional accommodation.

The new atrium was rectangular, the open court measuring some 14 m. from east to west and some 16 m. from north to south. A large part of the raised terraces on either side was removed and three porticoes were built, one on the east, with eight Corinthian columns in front of the basilica, and two at right angles to this along the north and south sides, each with six columns. The east colonnade was built on a low stylobate, that on the north on a low platform, all that was left of the raised terrace. At the west end a flight of four ascending steps led to three doorways which opened on another flight leading down into the street.

At the same time, presumably, the raised exedra in the middle of the outer north wall was converted into a circular chamber; the floor was considerably reduced in height and paved with mosaics; the floor of the room in the northwest corner was reduced in the same way. The pattern of the mosaics in the circular chamber was set out on the axis of the new portico in front of it, but the old line is indicated by insets in the surround in front of the side piers which were added where the Christian addition joined the classical building. In color and design the mosaics on this floor are some of the most pleasing in Gerasa. The design is based on a pattern which recurs in a circular panel in the north aisle of Procopius’ church, and is of special interest because it is set out in the same way as the plarn of the Dome of the Rock. There is one inscription in the center of the floor and a second running round the principal pattern. The second begins with the first three verses of Psalm 86 and ends with the words: “by the will of God the diaconia was built in the month of Artemisius in the thirteenth indiction in the year 627,”‘ a date which is equivalent to May, 565 A. D. The diaconia was explained in the Preliminary Report as being “probably an office where the deacons distributed charity to the poor of the city,” 5 but the word has other meanings, and it now seems to us more likely that this room was used for the reception of offerings.6

The natural level of the ground under the east court in which the basilica was constructed fell away towards the valley, and the court was partly built on an artificial embankment. Two massive walls ran east and west under the colonnades, broken only towards the east end by a tunnel which ran from north to south under the court. We may assume that the buildings on either side of the court connected by this tunnel stood on a lower level. The two colonnades in the court originally consisted each of fourteen, or possibly fifteen, columns. The columns stood on pedestals which rested on a high plinth; the capitals were Corinthian of a common second-century type without enriched abaci; the architraves had decorated soffits, but they were molded only on the inner side; the total height of the order was 7.03 m., including the architrave. At the east end the architraves of these colonnades were bedded in the wall of a triple gate which led from the court to the bridge beyond. At the west the colonnades ended just short of the lofty columns which led into the west court. The last architrave blocks are still lying on the ground, with return moldings across the short end faces. At present the ten western pedestals are still in position on the south side, but only seven remain on the north.

The space between the columns and the antae of the west court was presumably filled with blockage which has now fallen away. The two corners of the west wall are still buried under debris, but small sections of the north and south walls have been cleared a little farther to the east. These lateral walls are about 0.90 m. thick; they are poorly constructed of nari blocks which were plastered over both inside and out.

A small plain doorway was found on the north side opposite to the second bay from the west. On the south a better doorway with projecting jambs of maliki stone and plain splayed bases stood opposite to the fourth bay. Inside the church a few paving stones were found in position near each of the two lateral doors above mentioned. They show that the floor of this part of the church was on the same level as the classical court, though the stones were re-laid in the Christian period.

The east end of the church has suffered a great deal. The last four or five columns in both colonnades were overturned before the church was built, and several of the pedestals on which they stood were re-used in the foundations of the chancel.

The apse was inserted between the side walls of the triple gateway leading into the classical forecourt and constructed of old architectural blocks. Though these blocks appear to be solidly laid, the Christian building has been broken down to a much lower level than the classical walls on either side, and it is impossible now to be certain whether the apse was internal or whether it projected outside on a rectangular plan. Within the semicircle of the apse the ground level was raised at least 0.90 m. above the original paved floor, a part of which is still in situ.

The chancel extends about 12.2 m. into the nave in front of the apse, but it is narrower than the apse, being only 7 m. wide, and there is a space of 2 m. between it and the lines of the. two colonnades. The chancel was divided into two almost equal parts. In the east half, the part nearest the apse, there were the. foundations of structures on either side in which eight pedestals from the colonnades were used. The pedestals were laid on their sides and stood about 0.90 m. above the classical paving, which is again well preserved at this point. The west half is surrounded by the foundations of a chancel screen of the normal type with the usual grooves and sockets in it; the top of this is 0.60 m. above the original floor.

The one part not filled up was a place in the middle of the east half about 3.5 m. west of the apse. Here we found a large stone basin, 0.50 m. in diameter and rather less in depth, with four paving stones round it. The basin was obviously placed here when the floor was raised, that is to say, when the chancel was constructed, and inasmuch as a piscina or thalassa,. as it was technically called, was often placed under the altar as a receptacle for the water used in washing the sacred vessels and the hands of the celebrants. It marks the position once occupied by the altar, of which there is now no other vestige.

The chancel in this church may consequently be restored on the analogy of an early type of which several examples have recently been found in Greece and Macedonia.8 In these chancels the bishop’s throne, of which there is no sign in the Propylaea church, still occupied the center of the apse, which was higher than the rest of the chancel. The remainder of the synthronon, with its two rows of seats for the priests and deacons, was ranged along the east half of the north and south sides of the chancel. where in our church we find the higher foundations occurring. The. altar was put between them, well in front of the apse, in a place analogous to that of our thalassa. The west portion of the chancel, the solea, was enclosed, as in Gerasa, by a railing of the usual type.

Apart from the rather irregularly placed stones round the Thalassa, there was no trace of the chancel pavement. It was probably flush with the top of the foundation of the screen, that is, about 0.60 m. above the level of the floor at the. west end of the church. At the east end there are traces of a pavement on a rather higher level and it is possible that the chancel was, as is usually the case, only one step above the surrounding floor . Of chambers at the east end of the aisles no trace remains, and it is not unlikely that the aisles ended in doors like those in the. Prophets’, St. Theodore’s and the Synagogue church.

Carl H. Kraeling, Gerasa, City of the Decapolis; an Account Embodying the Record of a Joint Excavation Conducted by Yale University and the British School of Archaeology in Jerusalem (1928-1930), and Yale University and the American Schools of Oriental Research (1930-1931, 1933-1934) (New Haven, Conn.: American Schools of Oriental Research, 1938), 227–232.