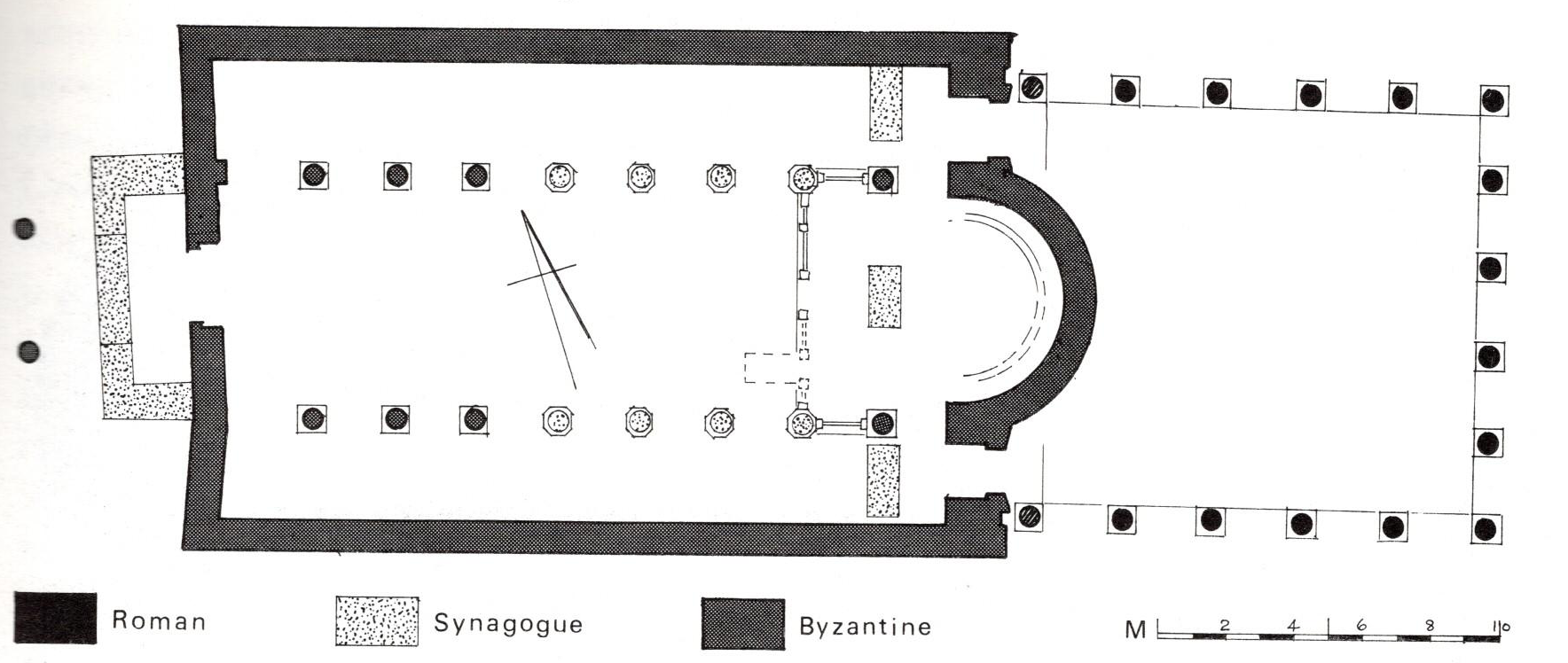

There are three phases at the site. There was an atrium at the east end of the site which may have been erected in the third or fourth century. West of this there. were the remains of a synagogue which was in use for a considerable period. A few centimeters above the floor of the synagogue were the remains of a church which was built in 530-531 A.D. and was also in use for a considerable period. Beyond this to the west was another court paved with plain mosaics.

An atrium in front of the main building in a religious precinct is a regular feature in Christian Gerasa, but there is no example of one aligned like the atrium at the east end of the Synagogue church, the two buildings meeting at the wrong point and at a wrong angle. The eastern atrium must therefore have been designed as part of some earlier complex.

The first traces of the synagogue were discovered at the east end of the later church some 0.15 m. below the floor. These were some mosaics forming part of a long narrow panel with a picture from the story of the Flood in the middle and a broad border around it. On the east side of the border there was a representation of the seven-branched candlestick, or Menorah, and other Jewish cult objects with an inscription in Greek which ended with the words: “peace to the congregation.” More mosaics on approximately the same level were found subsequently below other parts of the church floor, but the remains are fragmentary.

The church above the synagogue was built in 530- 531 A. D. when Paul was bishop. This date is all that is intelligible on the mosaic inscription in front of the chancel step, which was almost completely destroyed, presumably when the mosaics in the nave were mutilated by the adherents of a third religion. The dedication of the church is consequently unknown.

Churches and synagogues at this period had many features in common. Both were usually long buildings of the basilica type, both were designed for the needs of a congregation and for the celebration of services which were intimately related. They differed principally in orientation, synagogues being turned towards Jerusalem and churches normally to the east, in the direction, according to Gregory of Nyssa, of the Garden of Eden. It was an easy matter, therefore, to convert a synagogue into a church. The Christians removed the distinctively Jewish elements at the west end, they raised the level of the floor over the rest of the building, and adapted the east end to the ritual of the Liturgy.

The north wall of the church and the walls at each end of the north aisle are tolerably well built and may belong to Bishop Paul’s church, but the wall of the apse and the walls at the two ends of the south aisle contain some of the worst building we found in Gerasa. Of the south wall practically nothing remains; we looked for traces of a chapel against this wall but found none. There were two doors at the east end, one on either side of the apse as in St. Theodore’s. The door in the north aisle had old molded jambs, the other was botched together out of incongruous fragments. On the north side there were no doors and the south wall is so broken that it was impossible to distinguish any in it. At the west end there was a single entrance. In its present form it is of miserable cqnstruction and is probably a very late repair, but beneath it there are the foundations of broken walls and a mosaic floor in the middle of them with a pattern like that in the north aisle of St. Peter’s, broken by the present wall of the church.

The seven columns on either side of the nave which supported the synagogue roof were left standing on the original Jewish level, about two-thirds of the bottom section of the pedestals being consequently buried. At the east end another column was added on each side, on the line of the west wall of the Jewish vestibule, in order to support the roof above the new chancel. Two other pedestals of the same type carried the responds at the east end, and there is trace of a third respond on the north side of the west wall.

The nave was repaved with mosaics in the same style as the other churches of the period. The inscription was in the upper half of the panel which stretched almost the whole width of the chancel step, and, as is so often the case, underlay the ambo. A fret border ran round this panel, and in the lower half there was an acanthus scroll pattern which had been mutilated intentionally. The rest of the nave floor was surrounded by a fine scroll border in the restless florid style of the borders in St. John’s and St. Peter’s, and like them severely mutilated. Apart from a fragmentary inscription in the middle of the south aisle, only plain white mosaics were found here.

There was one step between the nave and the chancel which occupied only the central part of the east end. The screen had no entrance on the north side, but on the south side there was an opening which may have led to a sacristy on the far side of the south aisle. The ambo was in the normal place just south of the main entrance to the chancel; some fragments of the marble decoration of the ambo were found close to it. On the opposite side of the chancel, that is at the northwest corner, there were sockets which may have carried a table used perhaps in the Commemoration. The altar stood as usual on the chord of the apse.

Carl H. Kraeling, Gerasa, City of the Decapolis; an Account Embodying the Record of a Joint Excavation Conducted by Yale University and the British School of Archaeology in Jerusalem (1928-1930), and Yale University and the American Schools of Oriental Research (1930-1931, 1933-1934) (New Haven, Conn.: American Schools of Oriental Research, 1938), 234-36, 239-41.