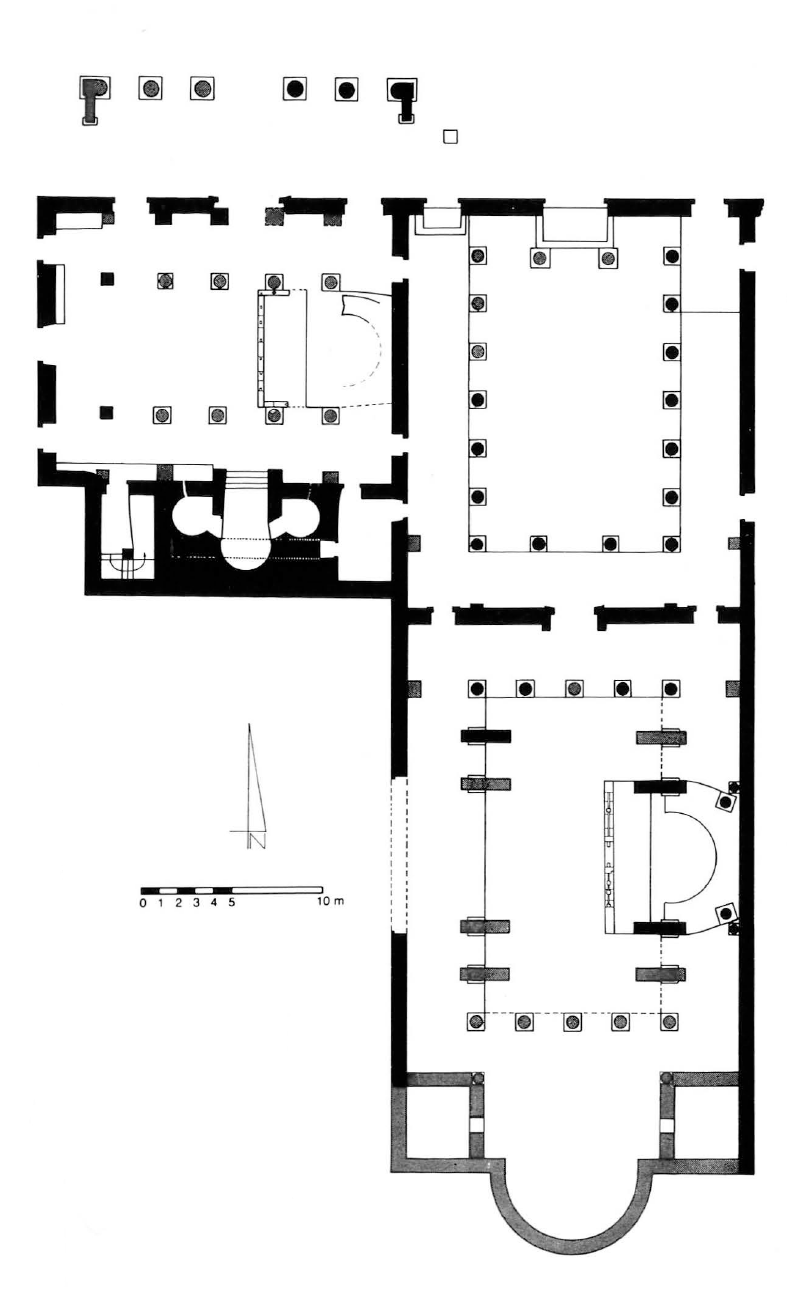

In one of his plans, M. de Vogue shows a church which was erected within a Pagan temple at Kanawat. The temple faced the north; it was prostyle, and terminated at the end opposite the entrance in a tri-Iobed apsis between rectangular side chambers.

The new three-aisled church was erected within this, with its major axis at right angles to that of the original building. It had five bays. An apse with side chambers (suggested perhaps by the arrangement of the Pagan building) was placed against and within the east wall of the temple, the tri-lobed apse was walled up, but the doorways of its side chambers were left to open upon the south side of the nave; the new north wall was erected upon the foundations of the front wall of the temple, and the beautiful portico of the temple became a side porch of the church. The new west front was set out a whole bay beyond the line of the west wall of the temple. It was made up in large part of fragments of an old Nabataean building and was very beautiful – the only beautiful west front in all the churches of Southern Syria.

Howard Crosby Butler, Early Churches in Syria: Fourth to Seventh Centuries, Princeton Monographs in Art and Archaeology (Princeton, N.J.: Department of Art and Archaeology, Princeton University, 1929), 24.

The pagan temple is one of the largest and most elaborately planned of all the ancient buildings in the Hauran. It bears traces of at least two periods of reconstruction within three hundred years after the original building. The great agglomeration of buildings forms an L, the foot of which is formed by the oldest part of the edifice. Among the walls, columns, and fragments of different styles, the details of this most ancient portion stand out in bold relief. The plan shows a temple-like structure-tetrastyle in antis-facing the north. The facade consisted of four columns, with a wide central intercolumniation, between two antae. Engaged columns appear on the inner faces of the antae, opposite the columns.

There is but one other feature of the Seraya that may be assigned to this period -the magnificent portal which now forms the entrance to the ruined basilical structure in the eastern part of the group of buildings. This portal in all its details is in keeping with the pronaos described above, and l do not hesitate to believe that it was removed from the front wall of the more ancient building, and set up in the later structure where it now stands.

The temple-like structure, then, with its portico, tetrastyle in antis, its apsidal south end, and this sumptuous doorway, must belong to a period of the highest development of art in the Hauran. From the lowness of its columns, the plain treatment of the bases, and the higher relief and greater freedom of the ornamental details, the temple should probably be placed earlier than the other two temples in this same town. There are further refinements about its carved ornament, especially in the treatment of the brackets upon its columns, and of the consoles beside the portal, which place it in advance of the temple at ‘Atil which dates 151 A.D.; and it is not impossible that the building may be even earlier than that date – a monument of that pure and elegant style which preceded the epoch of the Antonines. If this be true we may not be far astray in assigning the temple to the age of Trajan or of Hadrian.

Howard Crosby Butler, Architecture and Other Arts, Publications of an American Archaeological Expedition to Syria in 1899-1900, Pt. 2 (New York: The Century Co, 1903), 357–61.

Late in the third century, or perhaps early in the fourth, but still within the pagan period, the decline in architecture had gone so far in the Hauran that builders had begun to prey upon the monuments of preceding centuries for architectural details. This condition of things is manifest from a study of the so-called Seraya at Kanawat. the classic portions of which have been described on page 357. Many years after the completion of the prostyle temple, or whatever it may have been (see page 358), a large basilica was erected immediately to the cast of it, which included the eastern wall of the more ancient building in its structure. This building consisted of a colonnaded forecourt, or atrium, which extended along the entire eastern wall of the old edifice, and a basilica stretching to the south, having a semicircular apse in its south end.

Although some suggest that this was a Christian construction, the style of the columns of the portico, the construction and workmanship throughout, and especially the lack of orientation, would seem to forbid such theorizing, particularly in view of other work that was certainly carried on by the Christians in this same building and in a number of churches that are well preserved in the Hauran. The plan is not suitable to the: services of Christian worship; the colonnades which extend across the ends are far more in keeping with the arrangement of the pagan basilicas of the empire, and the chambers, which have no openings into the aisles, arc not planned in the fashion common in all the Christian churches of Syria; the building is not oriented, as the Christian houses of worship invariably were in Syria, judging by the multitude of examples: the walls, although they were built in large part of old material, were not laid in the manner most common in the churches of the neighborhood; and, finally. we know the building was remodeled a little latter to suit the requirements or the Christian architects

Howard Crosby Butler, Architecture and Other Arts, Publications of an American Archaeological Expedition to Syria in 1899-1900, Pt. 2 (New York: The Century Co, 1903), 402-405.

In the compact set of three large spaces, two basilicas and a courtyard with porticoes, called the “Serail”, but more traditionally “Nébi Ayoub” (“the saint man Job”), the first building examined here occupies the wing back to the west. Slightly elongated in plan, with three naves, this basilica is on the site of an ancient Roman building, of which it has preserved the north, east, and south walls. The orientation of the building has however been changed from north-south to east-west, and the new axis emphasized by advancing the facade towards the west. Three large doors open there, each designed by reused ornate blocks, and overlooking a nave. Of the three doors with which the original building was provided in its north facade, the two sides continued to be used; the widest door in the middle was undoubtedly condemned during the transformation of the building into a church, because two of the pilasters of the arches supporting the stone slab ceiling encroached on its splay. These doors opened towards the outside onto a portico raised in relation to the surrounding ground and street level, while west doors were preceded by a flight of steps and a landing. On the south side, the aisle runs along a set of three spaces. The first, to the W, contains the stairwell allowing access to the church galleries. The second is a triconch room which opens onto the aisle through a wide arc. We can recognize a martyrium organized there from what was perhaps the most old buildings of the complex in question. We access its podium, high, inclined and irregular, by a central staircase partly carved from its mass. The entrance, flanked by two low walls, was blocked by a chancel, or better still a grate, of which the embedding holes remain. A corridor underground running east to west in a cul-de-sac, which leaves from the east room, comes to an end under this podium.

The naves had six bays and led to a flat east wall. The last two bays of the central nave central are occupied by the sanctuary, of which nothing remains little more than the base of the chancel barrier and the back wall, flat, originally lit by a triple bay in height. On either side, at the end of the sides, a fairly narrow door opens to the E towards the courtyard porticos.

The pavement of the three naves presents what appears to have been two phases of basalt paving. The oldest is represented by the thresholds in the N wall and the row next to slabs, very poorly preserved, at the same level and showing the same degree of wear.

Pauline Donceel-Voûte and Bernadette Gillain, Les pavements des églises byzantines de Syrie et du Liban: Volume I : Décor, archéologie et liturgie, Publications d’histoire de l’art et d’archéologie de l’université catholique de Louvain 69 (Institut Supérieur d’archéologie et d’histoire de l’art Collège Érasme, 1988), 244–46.

Located behind the sanctuary of the eastern basilica, on the other side of the long north-south wall, is an important tomb 4.9 m wide by 7.5 m long, the floor of which is located 2.35 m lower as the paving of the sanctuary. According to the location chosen for this tomb and the fact that it is in largely made up of reuses, we can hypothesize that its first state is contemporary with the construction of the basilica or a little later, and that it is in any case in relationship with her. At the bottom of the tomb, and attached to the dividing wall with the basilica, is located a sarcophagus preceded by three steps and enclosed inside a sort of arcosolium . This sarcophagus, which contained five skeletons when it opened, is placed on a base made of a reused architrave block, which is identical to that of the prostyle order in front of the first west imperial building. The interior space of the tomb was vaulted: two pairs of pilasters and double arches received the barrel vault. We also see on the pilasters the reuse of bases and small pedestals of the same size and workmanship as the west imperial building. A another sarcophagus, which revealed a single skeleton, was installed on the paving, against the south wall, between the west arch and the first west pilaster. Its lid bears an inscription mentioning a priest of pagan worship. The shape of the letters makes it possible to date the inscription and the sarcophagus to the 3rd century. Either it is a reuse, or we can imagine that Christians worshiped the character contained in the sarcophagus to the point of to have reinstalled him in this tomb by giving a Christian meaning to the priestly reference. In a second state, the tomb was extended towards the east and closed by a door located in the middle of the east wall. He then received two other sarcophagi which were perched on the north and south walls of the tomb in a recess made for them. They are from the Christian era. The northern one (Fig. 51), where a skeleton was found, consists of a tank and a flat basalt cover. The face visible is decorated with two registers. The southern one offers the same type of decor with a few differences. Further south, two other tombs have been identified.

North of the Christian tomb, and also built against the long north-south wall, is a curious building, consisting of a small rectangular room measuring 2.40 m by 3.60 m, with which was accessed from the long eastern stoa through a door which was subsequently blocked. By elsewhere, on the north side, a door opened onto a paved corridor which surrounded the room on three sides

The “baptistery” is an elongated room measuring 4.20m by 11.70m which dates, in its last state, from the paleochristian phase of the buildings. Its paving which contained a reused inscription is at level of that of the stoa is of the quadriportic (Paleochristian level) and the threshold which makes it communicate with this stoa is of a corresponding height. The west and north walls are perhaps contemporaries of each other: their connection is however not clear. The east wall is added. The south wall collapsed. We see the remains of an east jamb of a door which may have existed in a state prior to the current state. This room was therefore probably built in the paleo-Christian era. on a pre-existing room whose eastern limits are unknown to us. Amenities interiors are interesting: in the northern part, we discovered a small pool dug in a column; in the southern part, a recess in the paving seems to correspond to the diameter of the basin now placed in the sanctuary. This double device is perhaps for liturgical purposes, However, the low depth of the basin and basin could only allow child baptisms.

Howard Crosby Butler, Architecture and Other Arts, Publications of an American Archaeological Expedition to Syria in 1899-1900, Pt. 2 (New York: The Century Co, 1903), 407-8.