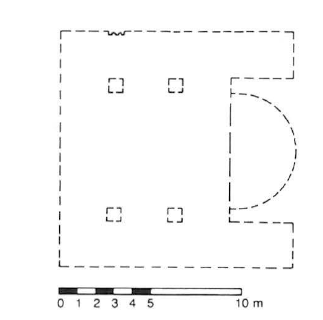

The remains of the building were buried under the houses of the current village. The church had three naves and a tripartite east end with two quadrangular sacristies on each side and on the other a semi-circular apse.

The proposed floorplan of the church is based on a diagram of distribution of mosaics drawn by M. B. Zouhdi, witness to the rescue operations and on the publication of Selim Abdul-Hak. The extensive commentary that Mr. Abdul-Hak was kind enough to give me on these various sources made this proposal possible.

We accessed the building from the E by the entrance to the dwellings modern. The construction was in large scale basalt, used for walls and piers.

The best preserved mosaics were in the east section of the three naves with only a few fragments of the representations coming from the chancel area.

Among the richly decorated mosaic floors we have scenes showing: a caravan with a camel driver (καμηλάριος), a man hunting for hares with two dogs, a man harvesting grapes, and a man with a cage, catching birds.

Several mosaic panels bear Greek and Syriac inscriptions. Two of them mention Saint George as the patron of the church:

The first reads: “O Lord, [Jesus of Saint] George (?), help [the] mosaicists who toiled here, and Prokopios, son of Raeos (?), regarding the laying of the mosaic.”

The phrasing of our mosaic is unusual. It invokes the help, probably of Jesus (or of God) ‘of Saint George’, not for the founder but first of all for the unnamed artisans who constructed the mosaic floor in this aisle. The identity of Prokopios mentioned in line 4 is not clear. He could be one of the artisans or the person who commissioned the mosaic and paid for it.

The second one reads: “+ As a vow for the salvation and the remission of sins of Petros, presbyter and abbot the present shrine (hierateion?) was paved with a mosaic and the rest of the church (naos) of Saint George. On the 20th (day) of the month of January, 5th indiction, the year 1033.”

The dedicatory formula mentions a certain Peter, presbyter and abbot, which implies that the church might have belonged to a monastery. More importantly, the inscription at the end of the north aisle provides a date for all the mosaics of the Saint George Church, 722 AD, a date at the height of the era Umayyad.

Pauline Donceel-Voûte and Bernadette Gillain, Les pavements des églises byzantines de Syrie et du Liban: Volume I : Décor, archéologie et liturgie, Publications d’histoire de l’art et d’archéologie de l’université catholique de Louvain 69 (Institut Supérieur d’archéologie et d’histoire de l’art Collège Érasme, 1988), 45, 53.

Donceel-Voûte believed that the inscription refers to the paving of an ‘infirmary’ (termed ἰατρεῖον, which is an otherwise unattested word, corrected by her from ἰατῖον) belonging to the church. This institution must have been located either directly in the east part of the north aisle where the mosaic was found (Donceel-Voûte points out that a part of the aisle was probably divided from the rest of the shrine by an enclosure), or in an adjacent chapel. As relics and reliquaries were often displayed in Syrian churches in chapels at the east end of north aisles, it is possible that the author of the inscription meant precisely such a chapel, where holy oil was distributed to ailing pilgrims, and not a proper ‘infirmary’, i.e. an institution offering beds and care to the sick. However, Denis Feissel prefers to read the disputed word as ἱ<ερ>ατῖον/’a shrine’, probably a chapel dedicated to the cult of George, which is a much more probable option.

Paweł Nowakowski, Cult of Saints, E01977 – http://csla.history.ox.ac.uk/record.php?recid=E01977