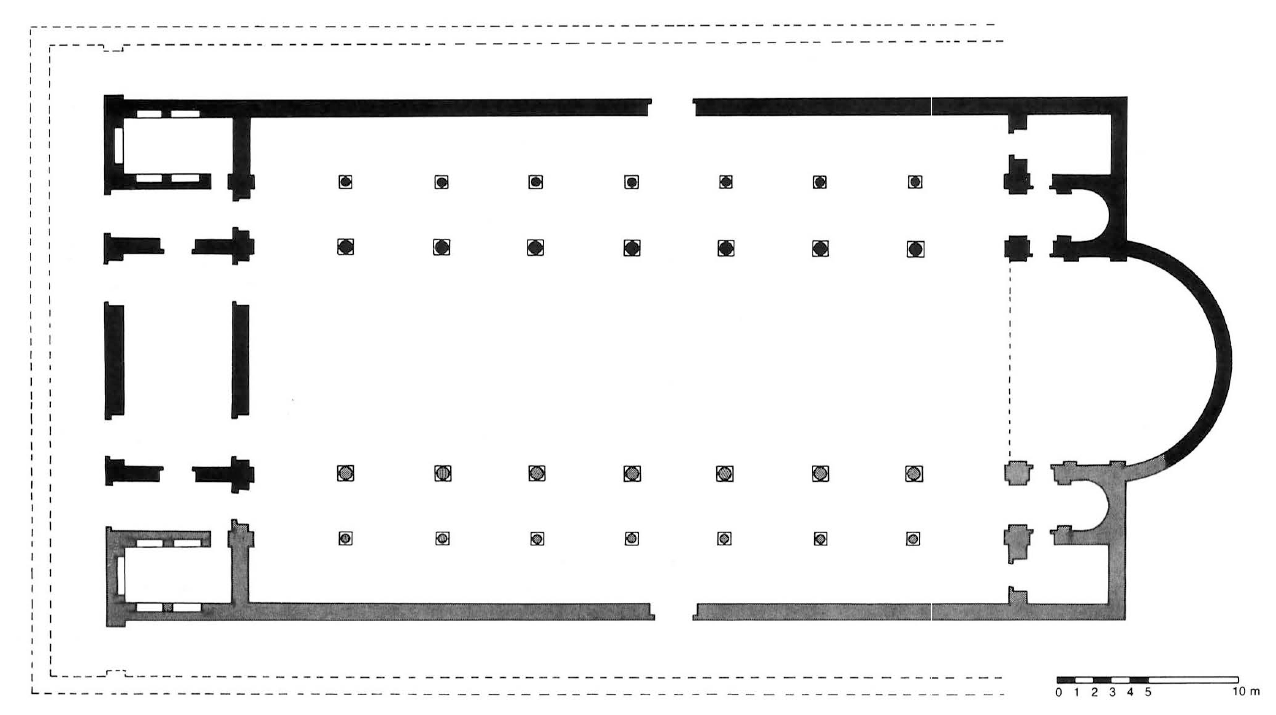

The church is now destroyed and is known only from the description of M. de Vogue. Only the external walls of the church were then preserved. M. de Vogue describes a large basilica with five naves of vast dimensions (67.60 x 41.85 m), whose interior aisles extend further towards the east than the outer collaterals and end with an apse inscribed on either side of a projecting semi-circular apse.

Anne Michel, “Églises à trois absides des provinces de Palestine et d’Arabie,” Syria 96 (2019): 167.

The north wall built of basalt like the whole building with its seven high arched windows, the west facade with the beginnings of the corner towers, part of the apse with the three windows of the apse, and a good part of the walls were seen by many travelers. Following the excavations of 1928, which concerned only the eastern part of the building, it was possible to establish the existence of five naves.

The apse is characterized by the large axial projection of the apse. The two well-preserved north sacristies are located behind a straight, common east wall, each at the end of an aisle. The north one is rectangular and is separated by a door from the aisle and by another from the neighboring room. The latter opens through a wide arch onto the internal aisle and through a door to the chancel; it consists of a short nave and an apse inscribed to the east.

From the central nave, we ascend towards a deep chancel, communicating via a door to the north and south with the two sacristies and opening to its full width onto the sanctuary in the apse. Colonnades separate the naves, with intercolumns measuring some 5.25 m and thicker shafts between the nave and the first aisles than in the external colonnades.

The narthex, which de Vogüé was able to establish was also organized into 5 compartments, was almost 6 m wide. Only the three central rooms give access to the naves and, to the outside, the middle one opens with two (and not three) majestic doors.

The Christian basilica seems to have been installed during the 5th century, but its monumental sculpture is mainly composed of reused.

Adjoining the basilica was a house and a small church, or chapel, with pillars carrying arches and a traditional roof of stone slabs.

It was quite difficult to determine the relationship between the ground levels discovered. The level of the mosaics in the intercolumnations is 0.95 m above that of the mosaics discovered in the adjacent aisle. It is therefore probable that the lower mosaics belong to a state preceding that of the Christian basilica. They were moreover disrupted by graves; However, if they had been visible in the pavement of the church, they would, without doubt, closed and repaved these locations. These late tombs probably exposed at the same level as the intercolumn mosaic and are from a second phase in the church.

Pauline Donceel-Voûte and Bernadette Gillain, Les pavements des églises byzantines de Syrie et du Liban: Volume I : Décor, archéologie et liturgie, Publications d’histoire de l’art et d’archéologie de l’université catholique de Louvain 69 (Institut Supérieur d’archéologie et d’histoire de l’art Collège Érasme, 1988), 308-09.